This eleventh part of the series on SageMath delves deeper into the RSA algorithm and demonstrates its implementation.

In the last article in this series on SageMath (OSFY, August 2025), we explored recent trends in quantum computing and how they are poised to impact cybersecurity in the near future. Our discussion also touched upon cryptanalysis and introduced the concept of public-key cryptography (PKC), along with a short program to help readers grasp the basic idea of PKC. As promised, this article will delve deeper into the RSA algorithm and demonstrate its implementation. However, before we proceed, it is important to address a foundational question. Throughout this series, we have seen how SageMath seamlessly integrates Python features. This may prompt some readers to wonder: Is SageMath simply Python with a few additional functions, merely masquerading as a distinct tool? The answer is a resounding ‘No’. In the following paragraphs, we will explore why SageMath stands on its own as a powerful and independent mathematical software system—far more than just another dialect of Python.

To understand why SageMath is more than just Python with a mathematical flair, we need to look at what it offers under the hood. At its core, SageMath is a unified, Python-based interface to a vast ecosystem of mature, open source mathematical software. This includes powerful tools like GAP (for group theory), PARI/GP (for arithmetic geometry), Maxima (for symbolic computation), Singular (for algebraic geometry), and many others. What SageMath does remarkably well is integrate these diverse systems into a single, consistent environment. This allows users to access their immense power without needing to learn each system’s individual syntax or quirks. Beyond this integration, SageMath also extends Python with its own rich set of native mathematical types and operations, providing a comprehensive and seamless experience for complex computations.

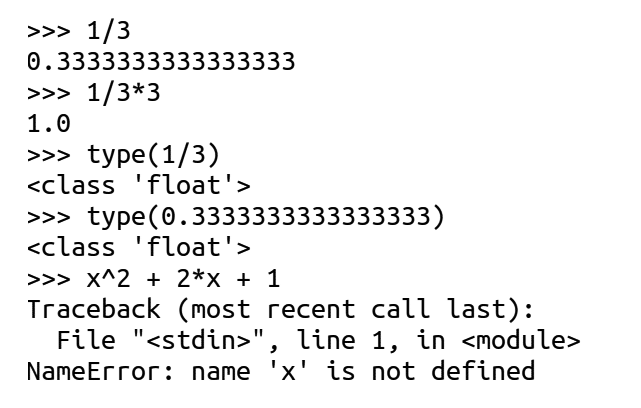

Figures 1 and 2 showcase five one-liners each from Python and SageMath, respectively, demonstrating their fundamental differences.

Now, let us compare the outputs produced by each one-liner shown in Figures 1 and 2. The first one-liner performs a simple division operation: 1/3. In Python 3, this results in a floating-point approximation: 0.3333333333333333. In contrast, SageMath interprets both operands as elements of the rational number field ℚ, and thus retains the result as the exact fraction 1/3 unless explicitly converted. This seemingly simple example illustrates a core philosophical distinction between the two systems: Python emphasises general-purpose programming with a focus on practical computation, while SageMath is designed for mathematical fidelity, preserving exact structures wherever possible.

Now, let us examine the second one-liner: the expression 1/3 * 3. In Python 3, the / operator performs floating-point division, so 1/3 evaluates to 0.3333333333333333. Multiplying this by 3 gives 0.9999999999999999, which is approximately equal to 1.0. This discrepancy arises due to the inherent limitations of floating-point arithmetic, where certain decimal values cannot be represented exactly in binary form. In contrast, SageMath treats numbers like 1/3 as exact rational numbers. So the expression 1/3 * 3 evaluates to exactly 1 without any rounding or approximation. This exactness is particularly useful in mathematical computations where precision is important, such as in symbolic algebra or number theory.

Now, consider the third and fourth one-liners involving type(1/3) and type(0.3333333333333333). In Python 3, both expressions are interpreted as floating-point numbers, and hence their type is float. This reflects Python 3’s default behaviour of using floating-point arithmetic for division. In SageMath, however, 1/3 is stored as an exact rational number and its type is Rational. On the other hand, 0.3333333333333333 is treated as an approximate real number, and its type is RealLiteral, indicating that it is a floating-point approximation.

Finally, the fifth one-liner in Python raises an error because Python doesn’t know what x is unless it is defined, and the character ^ represents bitwise XOR in Python, not exponentiation. In SageMath, the same one-liner works fine, as it interprets x as a symbolic variable and ^ as exponentiation.

These one-liners illustrate how SageMath enriches Python with deep mathematical knowledge, making it far more than just a wrapper or extension—it is a full-fledged system for mathematical computation.

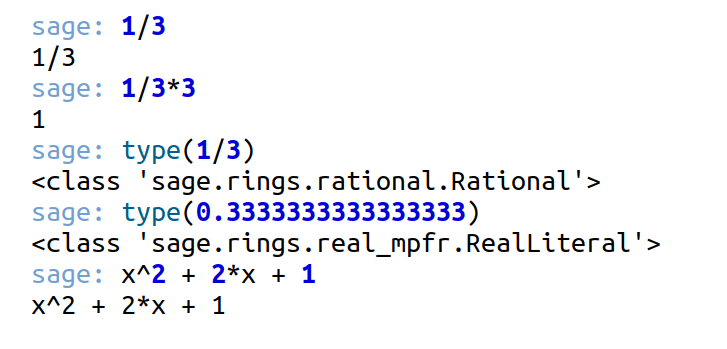

Let us now look at some examples where SageMath uses built-in mathematical functions that are not available in standard Python without importing external packages. The one-liners in Figure 3 demonstrate SageMath performing relatively complex mathematical operations with ease.

Now, let us understand the working of these SageMath functions. The SageMath commands in Figure 3 effectively demonstrate the system’s robust capabilities in symbolic and numeric computation, particularly in number theory and algebra. The initial command, Mod(a, b), swiftly computes the remainder of a very large number modulo, showcasing SageMath’s efficient handling of big integers. Following this, the function is_prime( ) reliably confirms that 1000000000000000000000000000000000000037 is indeed a prime number. The function factor( ) then expertly decomposes 1000000016000000063 into its prime components, 1000000007 * 1000000009, both being large primes. Subsequent operations, lcm( ) and gcd( ), further illustrate SageMath’s power: lcm( ) computes the least common multiple of these two primes, returning the original composite number, while gcd( ) confirms their coprimality (a property of two numbers that have no common factors other than 1) by yielding 1. Beyond integer arithmetic, the last one-liner highlights SageMath’s support for algebraic number fields through the function QQbar( ), representing the field of all algebraic numbers. When evaluating QQbar(sqrt(2)), SageMath returns an exact algebraic object, but its displayed numerical representation might include a trailing question mark (?) to indicate that this displayed value is an approximation (1.414213562373095?). This ability to naturally handle symbolic numbers and exact algebraic objects is another fundamental difference setting SageMath apart from Python, where similar functionalities would necessitate importing multiple external packages like SymPy, math, or mpmath.

In addition to its extensive native functionalities, SageMath often delivers faster execution when performing mathematical operations involving large numbers. This performance advantage becomes especially relevant in the context of cryptography, where computations with very large integers are fundamental to public-key encryption schemes.

Let us now consider an example where the speed advantage of SageMath over Python is evident. The Python program named ‘pythontime31.py’ shown below measures the time taken to compute the product of two very large integers. These large integers, stored in variables a and b, are generated by using exponentiation operations.

import time t0 = time.time() a = 2**10000000 b = 3**10000000 c = a * b print(“Wall time:”, time.time() - t0, “seconds”)

The SageMath program named ‘sagetime32.sage’, shown below, performs the same operations as the Python program ‘pythontime31.py’.

t0 = walltime() a = 2^10000000 b = 3^10000000 c = a * b print(“Wall time:”, walltime(t0), “seconds”)

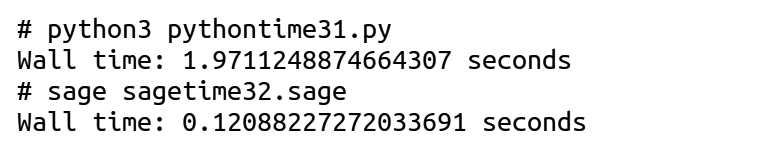

Notice that the two programs also illustrate the syntactical differences between Python and SageMath. For example, the programming languages use different operators for performing exponentiation (** in Python and ^ in SageMath). Upon executing the programs ‘pythontime31.py’ and ‘sagetime32.sage’, the outputs shown in Figure 4 are obtained. The outputs clearly show that the SageMath program runs roughly 16 times faster than the Python program, and as the sizes of numbers a and b increase, SageMath’s performance advantage becomes even greater.

Here’s an important question: Why is SageMath significantly faster than Python for numeric processing? One of the key reasons SageMath outperforms standard Python in many number-theoretic and algebraic computations is its integration with powerful low-level libraries like FLINT (Fast Library for Number Theory) and GMP (GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library). FLINT, written in C, is optimised for speed and designed specifically for number theory applications such as polynomial arithmetic, integer factorisation, and matrix operations over the integers and finite fields (all of them very relevant operations in public-key cryptography). GMP, on the other hand, provides high-performance arithmetic for large integers, rational numbers, and floating-point numbers with arbitrary precision (again very relevant in PKC). SageMath seamlessly connects to these libraries under the hood, giving it a significant computational advantage. In contrast, standard Python relies on the built-in int type and libraries like math or decimal, which are not designed for high-performance number theory or cryptographic workloads. As a result, SageMath handles very large number computations and symbolic algebra much faster and more accurately than vanilla Python (the standard, unmodified version of Python).

RSA under the microscope

Now, it is time to return to our discussion on RSA. In the previous article, we explored the history and background of the RSA algorithm. We will now move on to its implementation details. But before that, let us briefly recap what we have covered so far. In RSA, each user generates a pair of keys: a public key, which is shared openly, and a private key, which is kept secret. The public key is derived from two large prime numbers, but these primes themselves are never revealed. Anyone can use the public key to encrypt a message, but only the intended recipient—who possesses the corresponding private key—can decrypt it. This elegant asymmetry is what makes RSA a cornerstone of modern cryptography.

Now comes the important question: How large are the prime numbers used in practical implementations of RSA? Typically, RSA uses prime numbers that are 1024 bits (approximately 309 decimal digits) to 2048 bits (approximately 617 decimal digits) in size. A crucial part of the RSA public key is generated by multiplying two such large prime numbers. For example, in RSA-1024, two 1024-bit prime numbers are multiplied to form a 2048-bit semiprime—that is, a number that is the product of exactly two primes. This resulting number has about 617 decimal digits. While it is relatively easy to generate such a semiprime, factoring it back into its original prime components is computationally infeasible with today’s technology. Even the most powerful supercomputers would likely take hundreds of years to factor such a number using classical algorithms. This asymmetry is what makes RSA secure: multiplying two large primes is easy, whereas factoring the resulting semiprime back into its prime factors is extraordinarily difficult.

You can think of it like this: proving that unicorns exist is easy—you need to just show one. But proving that unicorns don’t exist requires exhaustive evidence, which involves searching every possible corner of existence. Similarly, finding the product of two primes is easy if you already have them, but discovering them from their product is practically impossible without a breakthrough in mathematics or quantum computing.

Let us now see how SageMath can be used to generate two prime numbers, each of size 1024 bits. Keep in mind that this is not a trivial task, as generating large primes requires efficient algorithms and careful handling of randomness. Fortunately, SageMath is equipped with powerful number-theoretic tools that make this process straightforward. The SageMath program titled ‘prime33.sage’, shown below, accomplishes this task.

p = random_prime(2^1024 - 1, 2^1023) print(“1024-bit prime (in decimal):”) print(p) print(“\nNumber of decimal digits:”, len(str(p)))

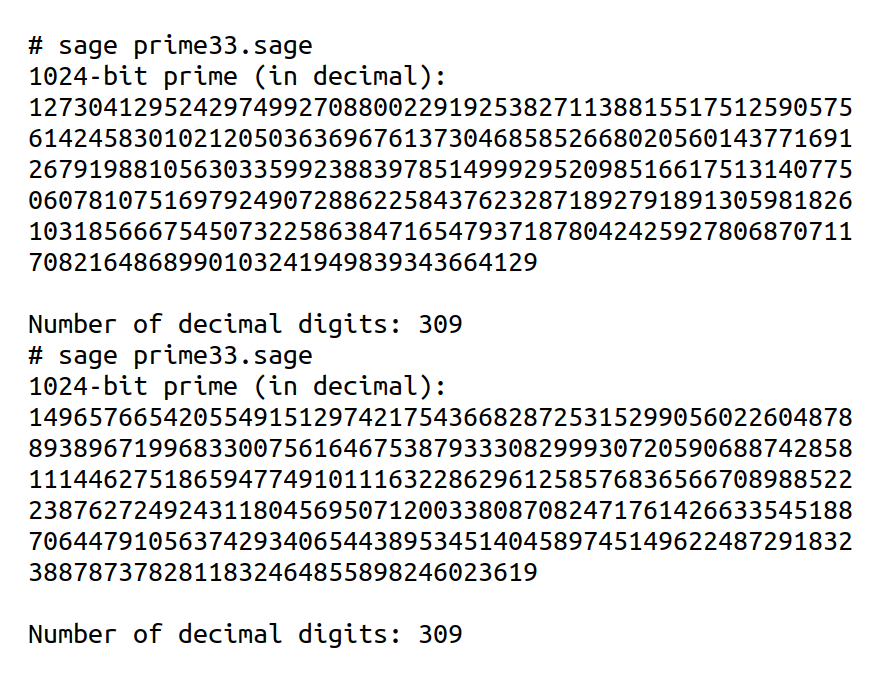

In the program, the first line calls the function random_prime( ) to generate a random prime number with exactly 1024 bits. This is achieved by setting the upper bound to 21024−1 and the lower bound to 21023, ensuring the resulting prime has exactly 1024 bits. The function random_prime( ) in SageMath relies on mathematical libraries like FLINT (Fast Library for Number Theory) and GMP (GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library) for high-performance large integer arithmetic and primality testing. The program is executed twice to generate the two required prime numbers. The output of each execution is shown in Figure 5. Notice that each 1024-bit prime number generated contains 309 decimal digits.

Now, let us implement a simplified version of RSA using the two 1024-bit prime numbers generated by the SageMath program ‘prime33.sage’. The SageMath program titled ‘rsa34.sage’ (line numbers are included for clarity), shown below, provides a simplified yet secure RSA implementation. Keep in mind that when running this program on your system, the variables p and q should be assigned the two prime numbers generated earlier. These assignment lines are omitted here to save space.

1. n = p * q 2. phi = (p - 1)*(q - 1) 3. e = 65537 4. d = inverse_mod(e, phi) 5. m = 68 6. c = power_mod(m, e, n) 7. decrypted = power_mod(c, d, n) 8. print(“Original message:”, m) 9. print(“Encrypted:”, c) 10. print(“Decrypted:”, decrypted)

Now, let us try to understand the working of the program. Line 1 computes the RSA modulus n, the product of two large prime numbers p and q. It forms the public key along with the exponent e. The value of n determines the size of the RSA key and sets the range for encryption and decryption. Line 2 computes Euler’s totient function φ(n) (called phi), which is used in calculating the private exponent d. It counts the number of integers less than n that are coprime to n—that is, their greatest common divisor (gcd) with n is 1. Line 3 sets the public exponent e. A common choice for e is 65537 because it is a prime number large enough to ensure security while being small enough to allow efficient encryption. Line 4 computes the modular inverse of e modulo phi, storing the result in the variable d. This is the private exponent, and part of the private key. Line 5 assigns the original plain text message to the variable m. In this case, it is the number 68, which corresponds to the ASCII code for the character ‘D’. Note that in real-world applications, m would be much larger or appropriately encoded before encryption. Line 6 encrypts the message and produces the ciphertext c using the public key (e, n). Line 7 decrypts the ciphertext and retrieves the original message using the private key (d, n). Finally, lines 8 to 10 print the original message, the encrypted message, and the decrypted message, respectively.

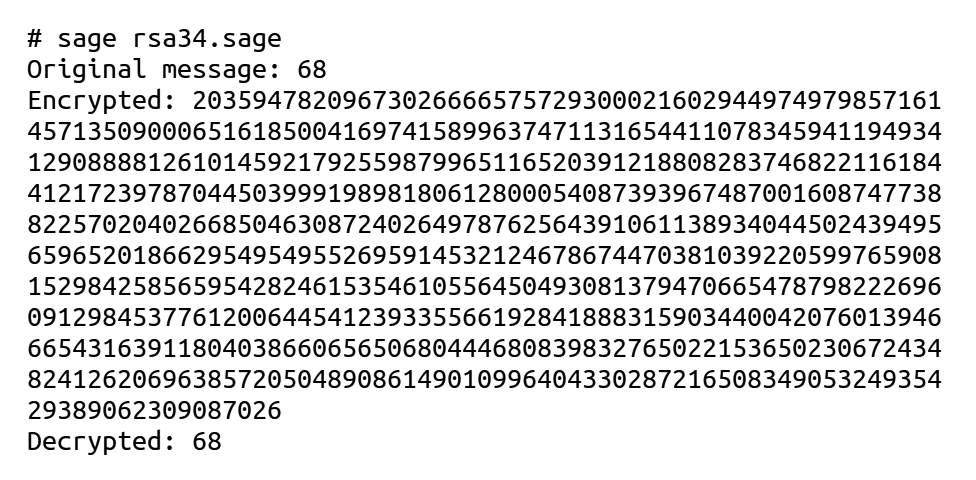

Upon execution of the program ‘rsa34.sage’, the output shown in Figure 6 is obtained. From the figure, it can be verified that decryption successfully retrieves the original message from the encrypted message.

Now, let us ask an important question: Why is the encrypted text so large, even when we are encrypting a small two-digit number like 68? Imagine placing a small object (our message) into an enormous safe (the modulus n). Even though the object is tiny, the safe must be huge to ensure security—and that is exactly how RSA is designed. RSA encryption transforms a message m into a ciphertext c using the formula c = m^e mod n, where e is the public exponent and n = p × q is the modulus, formed by multiplying two large prime numbers. In standard RSA-1024, the primes p and q are each 1024 bits long, making n approximately 2048 bits in size, or around 617 decimal digits. So, even if the message m is small, like 68, raising it to the power of e and reducing it modulo n naturally produces a ciphertext that spans the full range of n, potentially resulting in a very large encrypted value. This large ciphertext is not a bug; it is a necessary aspect of RSA’s design. The security of RSA relies on the computational difficulty of factoring a large semiprime, and to preserve this security, both encryption and decryption must operate within a very large number space.

This also highlights why RSA and other public-key cryptographic systems are not used to encrypt large volumes of data—they are computationally intense and suited only for encrypting small messages, such as secret keys. In practical systems, RSA is typically used to securely exchange a relatively short symmetric key, which is then used for fast, large-scale encryption with algorithms like AES. The topic of secure key exchange will be discussed in detail later in this series.

Now, let us discuss the practical security of RSA, particularly with 1024-bit keys. The security of RSA relies on the computational difficulty of factoring large semiprime numbers, that is, products of two large prime numbers. For RSA-1024, the most efficient known classical factoring algorithm is the General Number Field Sieve (GNFS). Even with massive computational resources—millions of CPU cores working in parallel—GNFS would take over 100 years to factor such a number. This makes RSA-1024 practically secure for most everyday applications, provided that the attacker is limited to classical computing methods.

The real threat to RSA lies in the potential of quantum computing. If a sufficiently large and fault-tolerant quantum computer were to be built, it could run Shor’s algorithm to factor the RSA modulus efficiently—possibly in just a few hours. However, as of 2025, this scenario remains entirely theoretical.

In summary, RSA-1024 remains practically secure against classical attacks, but it is no longer considered future-proof due to advances in quantum computing research. For high-security applications, RSA with 2048 or 3072 bits—or quantum-resistant algorithms—are increasingly being recommended to ensure long-term protection.

Now it is time to wrap up our discussion. In this article, we explored how SageMath is much more than just another Python dialect. We looked at several examples where SageMath outperforms standard Python, thanks in part to powerful libraries like FLINT and GMP. We concluded with a discussion and implementation of RSA encryption. In the next article, we will continue our journey into public-key cryptography and take a closer look at the underlying mathematical libraries.