Coq and Lean are tools that elevate trust in research and software development with rigorous proofs. They also help to prove that code is bug-free.

It is undenible that the open source software movement is affecting the world positively. But how exactly does open source software impact human lives? First and foremost, it offers popular software for free (free as in ‘free beer’). Nowadays, you don’t have to pay for an operating system or a word processing package. There are tons of open source software freely available for you to choose from. This shift has also prompted software giants to offer their software at relatively lower prices to remain competitive.

However, the impact of open source software extends far beyond this. For instance, the research community in various fields, including science, engineering, technology, management, and social sciences, has greatly benefited from the open source software movement. Notable examples include software like Scilab, SageMath, Project Jupyter, LaTeX, and Python libraries like NumPy and SciPy, among others. The list is so extensive that attempting to enumerate all of them would be futile. In fact, I think I have left out many important names from the list. What makes this even more fascinating is the fact that the open source community boasts some of the world’s most brilliant minds contributing as programmers and software engineers—talent that even the largest software companies can only dream of employing. As a result, highly specialised and technical software has been developed to cater to the needs of communities engaged in top-class research in science, engineering, and technology.

In this article, we will acquaint ourselves with one such category of software: interactive theorem provers.

Undoubtedly, all of us have had to prove some theorems in our lifetime, with the Pythagorean theorem being a prime example. But why do we need interactive theorem provers? Imagine that you are a researcher confident of proving an essential theorem. However, how can the research community fully trust your proof? There might be an unnoticed error in your reasoning. This is where peer review comes to our rescue. To gain credibility, you must submit your proof to a reputable journal, where experts in your specific area of research will evaluate your work and verify its accuracy and authenticity. However, human error can still creep in, and indeed, such issues have occurred in the research community on numerous occasions.

The history of the four-colour theorem

Let us briefly go through the history of the famous four-colour theorem as an example of erroneous proofs being mistakenly accepted as correct. The four-colour theorem states that no more than four colours are required to colour the regions of any map so that no two adjacent regions sharing a boundary will have the same colour. Notice that if two or more regions meet only at a point, then they can share the same colour. Figure 1 shows an example of a map coloured in just four colours (Courtesy: Wikipedia). The observation was first made by Francis Guthrie in 1852. In 1879, a proof was proposed by Kempe. This proof was widely accepted as correct. However, in 1890, Heawood proved that Kempe’s proof was incorrect. Notice that an incorrect proof was believed to be true for almost 11 years.

The work by Kempe was used by Heawood to prove a weaker theorem known as the five-colour theorem. After many false and incomplete proofs and almost a century later, the four-colour theorem was finally proved in 1976 by Appel and Haken. However, their proof was computer-based, and due to the immense size of this proof, its veracity was still doubted by many. A simpler proof using the same ideas (again relying on computers) was published in 1997 by Robertson, Sanders, Seymour, and Thomas. Finally, in 2005, the theorem was proved by Werner and Gonthier using Coq, thus ending any doubts about the proof of the theorem. Now, we can place our trust solely in the Coq kernel. So, in a nutshell, an interactive theorem prover can be a powerful tool in establishing the validity of complex theorems.

In this article, we will only introduce two interactive theorem provers: Coq and Lean. Although the article will not delve into the details of these two software, it will serve an essential purpose. The readers will become aware of the abundance of solutions offered by the open source software community, and they will also realise that solutions may exist even for the most difficult problems.

Coq

Coq is free and open source software developed by INRIA, a French research institute focusing on computer science and applied mathematics. Coq operates under the LGPLv2.1 licence. It was first released in 1989, and the latest stable version is version 8.17.1. Figure 2 shows the logo of Coq. As mentioned earlier, a definitive proof of the four-colour theorem is one of the early success stories of Coq. The Feit–Thompson theorem is another important theorem proved using Coq. Coq was developed using Ocaml, which is a multi-paradigm programming language with emphasis on functional programming.

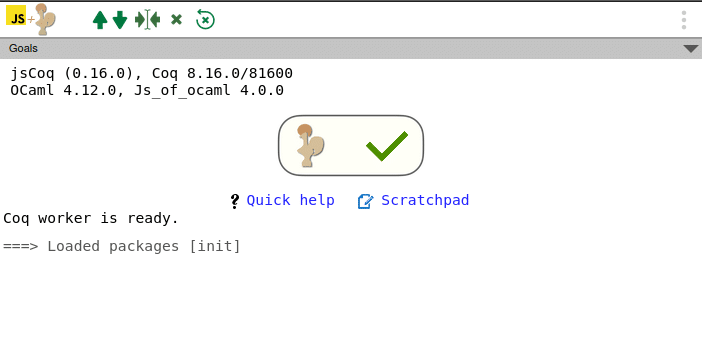

Now, let us see how to use Coq from our system. One good thing is that you don’t need to install Coq on your system to work with it. You can run it in your browser using a web-based environment called jsCoq. This environment is available online at https://coq.vercel.app. Figure 3 shows the terminal of the jsCoq environment. For beginners, I suggest using this web-based environment.

However, Coq is also cross-platform software; it can be installed and used on Windows, macOS, and Linux. In Linux, Coq can be used with different interfaces like Vim, Emacs, etc. As an example, we will see how to install and use Coq in Ubuntu. I have used Proof General, an Emacs interface for Coq. Usually, Emacs is installed in Ubuntu by default; otherwise, you need to install Emacs on your system. Emacs, Proof General, and Coq can be installed on your system by executing the following three commands in the terminal:

sudo apt install emacs sudo apt install proofgeneral sudo apt install coq

Now, open the Emacs terminal by executing the command ‘emacs’ in the terminal. From this point onwards, we have to use some basic Emacs commands to use Proof General and Coq. This is the reason why I recommended the web-based jsCoq over Proof General for working with Coq. In this way, some of the complexities associated with Emacs can be avoided while handling the intricacies of Coq. However, notice that the Coq syntax used is the same in both these environments.

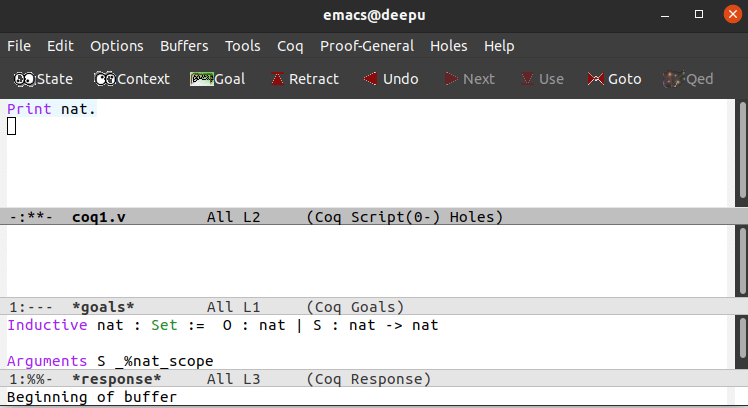

Once the Emacs terminal is opened, press ‘Ctrl+x’ and then ‘Ctrl+f’ to open a file in Emacs. When prompted, give a name to the Coq file in which your Coq source code should be saved. In this example, I have used the file name ‘coq1.v’. Notice that Coq files have a ‘.v’ extension. Now, you will see Proof General coming into action. Figure 4 shows the window of Proof General displayed when a Coq file is opened.

Later, a file named ‘coq1.v’ will be opened in the Emacs terminal. In the file, enter the following line of code: ‘Print nat.’ to print the definition of ‘nat’. Keep in mind that Coq is case-sensitive, and the dot (.) after the code ‘nat’ is mandatory. Now, on the Emacs terminal, press ‘Ctrl+c’ and then ‘Ctrl+n’ to run the next step in the Coq program. Since there is just one line in our Coq program, that line will be executed, and the output will be displayed. Figure 5 shows the Emacs terminal when this simple Coq program is executed. The same line of code can also be executed in the web-based environment jsCoq.

The following Emacs commands are also useful for processing Coq programs. To go to the previous step in a Coq program, press ‘Ctrl+c’ and then ‘Ctrl+u’. Press ‘Ctrl+x’ and then ‘Ctrl+s’ to save the changes made to the current Coq program being edited. Finally, press ‘Ctrl+x’ and then ‘Ctrl+c’ to close the Emacs terminal. After executing this command, type ‘yes’ when prompted to quit.

But what is the meaning of the output shown in Figure 5, which is obtained when the single line of Coq code got executed? The line of code on execution prints the definition of natural numbers (the set of numbers 0, 1, 2, …, denoted by the symbol ℕ). Notice that if you are using jsCoq, when you type ‘nat’ on the environment, it is automatically replaced with the symbol ℕ. From the definition printed on the terminal, we can see that 0 is defined as a natural number and the successor of a natural number is also defined as a natural number. Thus 1 is a natural number because 0 is defined as a natural number, and so on and so forth. This definition is based on the Peano axioms for natural numbers. To keep things simple, I will refrain from introducing any technical terms in the rest of our discussion. Further, it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss even simple Coq programs proving very basic theorems like De Morgan’s laws. Therefore, we conclude our discussion of Coq by highlighting its main components and the strategy used in giving proofs using Coq.

Coq involves two types of commands: ‘vernacular’ and ‘tactics’. Vernacular commands allow interaction with the Coq environment and include commands like Theorem, Lemma, Fact, etc. Tactics, on the other hand, are used to interact with the proof state and guide the proof process. They apply various proof strategies, such as simplifying expressions, applying logical rules, performing case analysis, and introducing hypotheses. Examples of tactical commands include intros, rewrite, and destruct. Coq also provides a specification language called Gallina. Interestingly, the word ‘Coq’ means ‘rooster’ in French, while ‘Gallina’ means ‘hen’ in Latin. Additionally, Coq has a built-in tactic scripting language called Ltac, which automates and customises the proof process. While Ltac is widely used with Coq, it is not often considered a standard part of Coq.

Now, let us discuss the strategy used in Coq to prove a theorem. Coq provides constructive proofs. It has a type called ‘True’, which consists of the set of all provably true propositions. Thus, in Coq, if you can find a value for a type, then it is considered proved. For example, the type ‘nat’, as seen in the line of code discussed earlier, proves that natural numbers do exist. The proof strategy in Coq follows this approach: a required theorem to be proven is denoted as a type. A proof for this theorem involves deriving a value for this type based on fundamental facts. This proof strategy also ensures that a false value can never be derived in Coq. The reason is that a value of ‘False’ is impossible to construct in Coq.

Lean

Now, let us turn our attention to Lean. Nowadays, we frequently encounter the names of companies known for developing proprietary software even when discussing free and open source software. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that Lean, the second interactive theorem prover we are discussing in this article, is developed by Microsoft Research. The project, primarily developed by Leonardo de Moura, was first released in 2013. Lean is free and open source software licensed under the Apache License 2.0. Figure 6 shows the logo of Lean.

At present, there are two versions of Lean available: Lean 3 and Lean 4. However, it’s important to note that Lean 4 is not compatible with Lean 3, meaning that code written for one version may not work in the other. One of the standout features of Lean is its powerful mathematical library known as mathlib. Initially, Lean 4 encountered issues when utilising this library, but these have now been resolved, and Lean 4 can seamlessly use mathlib as well. If you prefer to use Lean 4 without installing it in your system, you have the option of utilising a web-based environment accessible at https://lean.math.hhu.de. However, should you decide to install and run Lean 4 on your local machine, the most straightforward approach is to use the Visual Studio Code editor (VS Code editor). Although I won’t delve into the detailed steps for setting up Lean 4 in VS Code editor here due to space constraints, I assure you that the installation and usage process is remarkably easy and straightforward.

Now, let us explore how Lean 4 code can be executed in both the VS Code editor and the web-based environment. Take a look at the line of code ‘#check 5 + 5’. Notice that Lean programs are saved with a ‘.lean’ extension. When you run this code, it will produce the output ‘5 + 5 : Nat’, confirming that the number 10 is also a natural number.

It is time to wind up this article, but before we conclude our discussion, two important questions need to be addressed. First, are there any notable distinctions between Coq and Lean in their approach to obtaining a proof? I have been informed that Lean is better suited while using classical logic to derive a proof. However, Coq has a larger and older community around it when compared to Lean. Nevertheless, any disparities between the two will diminish over time since both software packages are experiencing rapid development. Second, are there any other applications for interactive theorem provers aside from proving theorems? Absolutely! Both Coq and Lean can be used to provide guarantees for the programs you have developed. Rather than relying on test cases to verify a program’s correctness, you can utilise Coq or Lean to formally prove that the program is free of bugs.