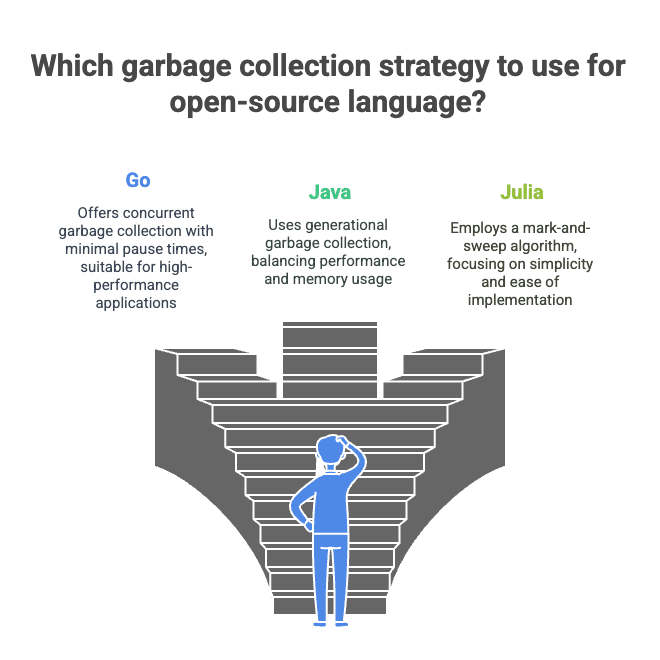

Explore how three open source languages—Java, Go, and Julia—take different paths to solve the invisible challenge of garbage collection. Whether you’re working with enterprise apps, cloud-native systems, or scientific models, knowing how each language manages memory can help you make better technical decisions.

What happens to your app’s memory once it’s no longer needed? Most developers don’t think about it until performance drops, latency spikes, or crashes creep in.

That’s where garbage collection strategies come into play. The way a language handles memory cleanup behind the scenes can quietly shape how fast, reliable, and scalable your software becomes.

Garbage collection isn’t about cleaning memory—it’s about keeping your software breathing under load.

What is garbage collection?

Garbage collection (GC) is a form of automatic memory management. It’s a process that runs in the background of many programming languages, finding and cleaning up memory that’s no longer needed so developers don’t have to do it manually.

Without garbage collection, unused memory can pile up, leading to memory leaks, slower performance, and system crashes. GC helps prevent this by making sure memory is freed up when objects or data are no longer in use.

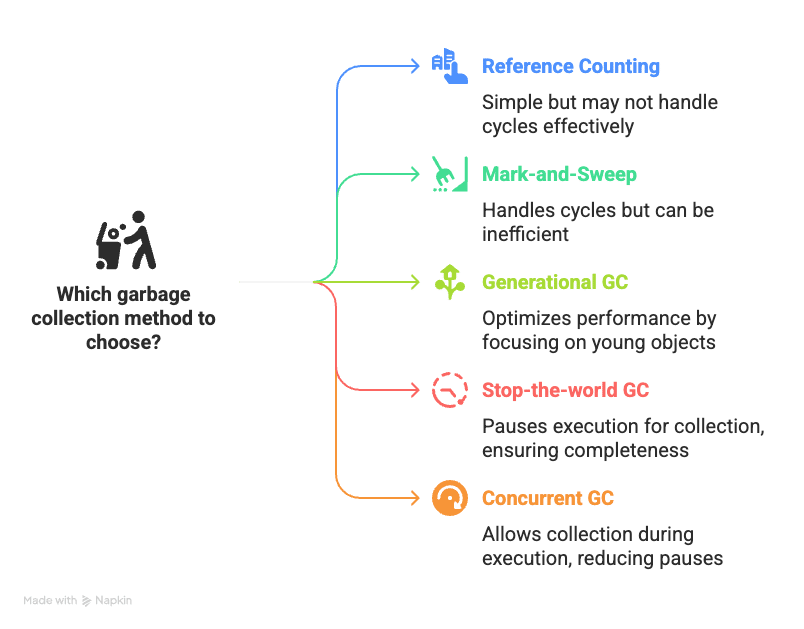

Common garbage collection methods are:

Reference counting: Keeps track of how many parts of the program are using a piece of data. When the count drops to zero, the memory can be freed.

Tracing (mark-and-sweep, generational):

- Mark-and-sweep scans memory to mark active objects and then clears the rest.

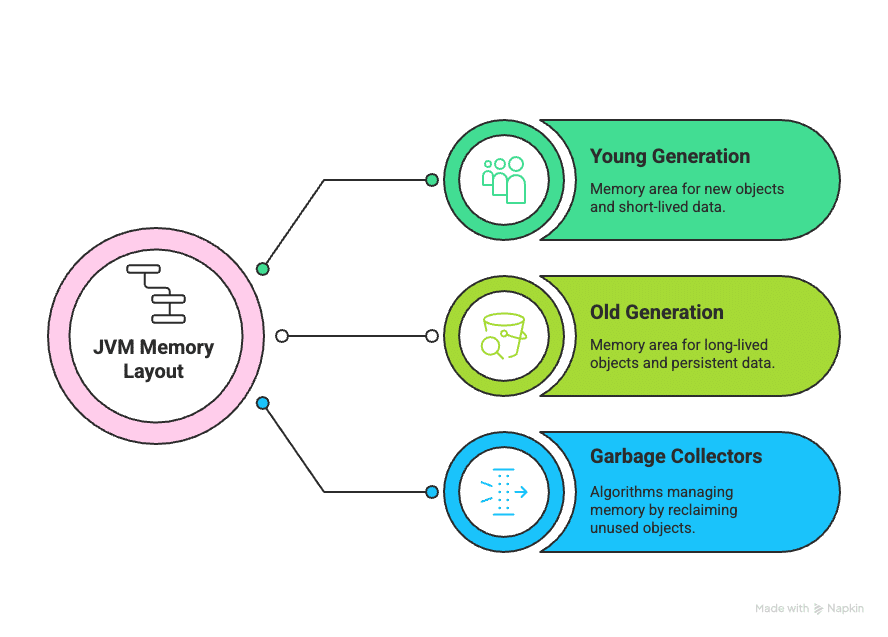

- Generational GC splits memory into ‘young’ and ‘old’ objects, optimising how often each part is cleaned.

Stop-the-world vs concurrent GC:

- Stop-the-world pauses the entire program during garbage collection.

- Concurrent GC runs alongside the program to reduce pauses and improve responsiveness.

Java GC: Strengths vs weaknesses

| Aspects | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| GC algorithm options | Multiple choices (Serial, Parallel, CMS, G1, ZGC, Shenandoah) for different needs | Requires knowledge to choose the right GC for your app |

| Performance tuning | Can optimise for either high throughput or low pause times | May involve trial-and-error tuning and detailed benchmarking |

| Observability and tooling | Rich tools (JVisualVM, GC logs, Flight Recorder) for monitoring and debugging | Tools require setup and understanding of JVM internals |

| Scalability | Handles large heaps and multi-core systems efficiently | GC tuning may become more complex as system scale increases |

Java’s garbage collection strategy

Java runs on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), and one of its biggest strengths is the flexibility it offers in memory management. The most used JVM, HotSpot, supports multiple garbage collection algorithms—each tuned for different needs like low latency, high throughput, or minimal pause times.

Modern enterprise applications — whether cloud-based microservices, SaaS platforms, or high-frequency trading systems — require predictable performance, scalability, and stability. Java’s diverse garbage collection strategies offer tailored solutions:

- Low-latency, real-time apps benefit from ZGC and Shenandoah.

- Large-scale services with high throughput leverage G1 and parallel GC.

- Small, embedded apps can still efficiently run on serial GC.

Java’s GC makes it ideal for:

- Enterprise backends

- Large-scale web services

- Android applications

- High-performance financial systems

Go GC: Strengths vs weaknesses

| Aspects | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Concurrent collection | Runs GC alongside the application, reducing pauses and maintaining responsiveness | May lead to less control over when and how GC occurs compared to Java |

| Low-latency goal | Sub-millisecond pause times, ideal for performance-critical applications | Longer or more frequent pauses may still happen in high-load scenarios |

| Automatic tuning | Minimal configuration required from developers | Less fine-grained control for tuning memory management |

| Evolving technology | Continuous improvements since Go 1.5, making it more efficient with each release | Still not as mature as Java’s GC options and may not fit all use cases |

Julia GC: Strengths vs weaknesses

| Aspects | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| GC design | Optimised for short-lived objects, typical in scientific computing | Stop-the-world GC with high pause times can be disruptive in real-time apps |

| Tied to JIT compilation | Strong integration with Julia’s JIT execution model for numerical computing | GC performance and behaviour are tightly linked to JIT, limiting flexibility |

| Tuning and control | Simple memory management with less overhead for developers | Fewer tunable options compared to Go and Java, limiting optimisation choices |

| Use case optimisation | Excellent for numerical computing, data science, and machine learning | Not ideal for latency-sensitive applications or long-running services |

Go’s garbage collection strategy

In Go, garbage collection automatically reclaims memory that is no longer reachable or needed by the program. When a Go program creates objects in memory (allocated on the heap), these objects may eventually become unreachable. Go’s garbage collector identifies such objects and frees up their memory — ensuring developers don’t have to manually allocate or deallocate memory like in C or C++.

The result:

- No memory leaks (in most cases)

- No dangling pointers

- Safe concurrency without manual memory management headaches

Let’s break Go’s garbage collection strategy into clear components.

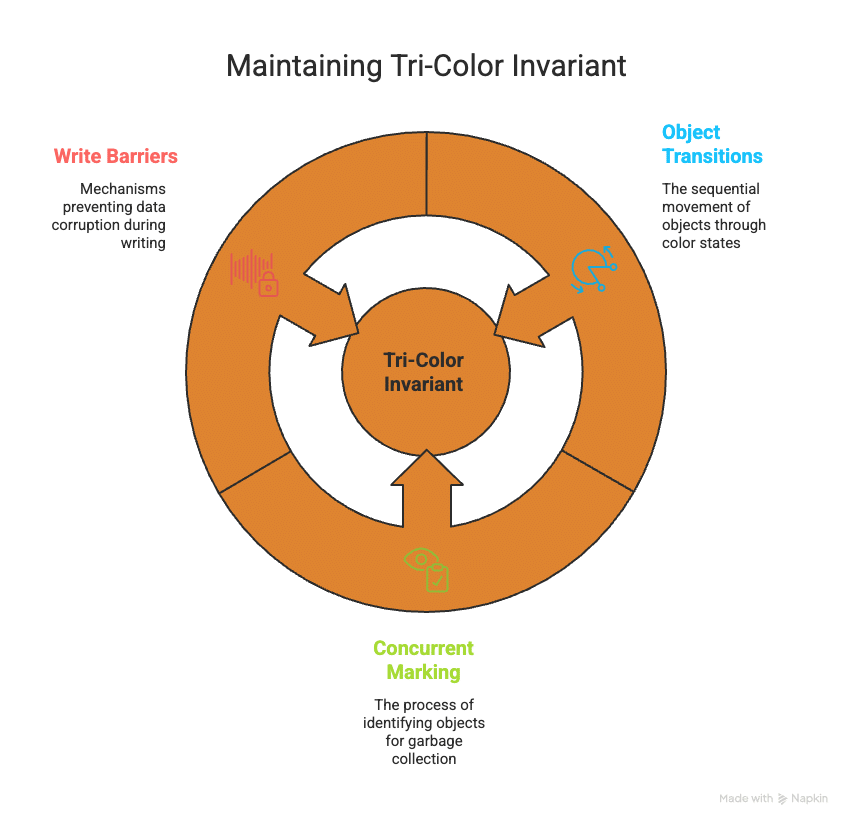

Tricolor marking algorithm: Go’s GC uses a tricolor marking abstraction to track object reachability. Objects are conceptually coloured:

- White: Unreachable (candidate for garbage)

- Gray: Reachable but not yet fully scanned

- Black: Reachable and fully scanned

The collector traverses all reachable objects starting from roots (global variables, stack pointers, etc), moving objects from gray to black, and eventually clearing away white (garbage) objects.

Concurrent mark and sweep:

- Mark phase: Runs concurrently with application goroutines.

- Sweep phase: Also incremental and concurrent, freeing memory progressively.

- Minimal stop-the-world pause is required at the start and end to ensure safe root marking and clean-up.

Write barrier (tricolor invariant maintenance): To safely run GC concurrently with mutator threads (the running program), Go uses a write barrier — a mechanism that intercepts pointer writes to ensure the tricolor invariant isn’t violated. This guarantees correctness even as the program continues to modify memory during a GC cycle.

Go’s GC is ideal for:

- Web services

- Cloud infrastructure

- Containerised environments

Julia’s garbage collection strategy

Julia uses a mark-and-sweep garbage collector, which identifies and frees memory occupied by objects that are no longer in use. However, unlike Java and Go, Julia’s GC is stop-the-world and not generational (as of the latest stable versions). This means that during garbage collection, the entire program halts until the cleanup is finished.

The benefits:

- No need for explicit memory deallocation (like in C/C++)

- Reduced risk of memory leaks and dangling pointers

- Safer and simpler code, especially in complex numerical and scientific computations

Julia’s garbage collection strategy is a stop-the-world, mark-and-sweep collector — conceptually simple but highly optimised for performance. Let’s break that down:

Stop-the-world: When a garbage collection cycle runs, Julia pauses all running threads to ensure memory safety. During this pause, no Julia code executes — only the garbage collector is active.

While stop-the-world strategies can introduce latency, Julia’s GC is engineered to minimise pause times for typical workloads. For many numerical computing applications, brief but infrequent pauses are acceptable trade-offs.

Mark-and-sweep algorithm: Julia’s GC operates in two main phases:

- Mark phase: Starting from GC roots (global variables, stack frames, etc), the collector traverses all reachable objects and marks them as ‘alive’.

- Sweep phase: Once marking is complete, the collector scans through allocated memory and frees any unmarked (unreachable) objects, returning that memory to the allocator.

This method ensures that only unreachable objects are deallocated, preventing accidental memory reclamation of live data.

Julia’s GC is particularly suited for:

- Numerical computing: Performing calculations and simulations with numbers.

- Data science: Analysing and interpreting complex datasets for insights.

- Machine learning: Developing algorithms that learn from data automatically.

Comparative analysis: Go vs Java vs Julia

Garbage collection isn’t just a behind-the-scenes detail—it directly shapes the performance, reliability, and scalability of modern software. As we’ve seen, Java offers a mature, configurable GC ecosystem ideal for enterprise and large-scale systems. Go takes a modern, hands-off approach, favouring concurrency and simplicity for cloud-native applications. Julia, while less mature in its GC implementation, prioritises performance for scientific workloads and high-throughput numerics.

Each language reflects a different philosophy:

- Java empowers developers with control.

- Go minimises GC complexity for developer focus.

- Julia optimises for computational intensity, even with some GC trade-offs.

In the end, the best GC strategy is not universal—it depends on your application’s real-time needs, resource constraints, and performance goals. Understanding how these languages manage memory helps you not only write better code but also choose the right tool for the job.