In this final article of the 12-part series on AI, we will briefly review the topics covered thus far and suggest how to continue improving our skills. Additionally, we will discuss the main topics that were not adequately covered in the series and offer guidance on how to master them. However, the primary focus of this article will be on programming languages, other than Python, that are widely used for developing machine learning-based applications.

As we arrive at the final article in this series on AI and machine learning, I am reminded of a quote by Winston Churchill that aptly applies to the journey of a newcomer introduced to AI through this series: “This is not the end, this is not even the beginning of the end, this is just perhaps the end of the beginning.” While we have covered a great deal in this series and gained valuable knowledge, this is only the start of our journey in the vast ocean of AI. To navigate these challenging waters, we must still acquire a multitude of skills.

Let us begin this final article by taking a moment to review the latest trends in the fields of AI and machine learning.

For a while, there were various online and offline tools that claimed to use AI to perform diverse tasks. However, not many people took these tools seriously. For example, the AI-based image generation model DALL-E 2 has been active since January 2021. However, tools of this kind gained prominence after ChatGPT was launched. Suddenly, hundreds of AI-based tools came into the spotlight. Let us take a look at some of them.

The first one is Bard, developed by Google and launched in March 2023. It is a chatbot based on the LaMDA family of large language models and aims to compete with ChatGPT. However, as of April 2023, Bard is not yet available in India. In

my observation, ChatGPT provides only subpar performance while answering advanced mathematical questions — not simple arithmetic. Therefore, I am eagerly waiting to compare Bard with ChatGPT. Bard is just the beginning — almost every tech giant has announced or introduced chatbots to compete with ChatGPT. Let us discuss a few more of them. LLaMA (Large Language Model Meta AI) is a large language model developed by Meta (Facebook). Although launched in February 2023, you have to request access and wait to use LLaMA. This is another tool I am eagerly waiting to try out.

IBM Watson from IBM and Ernie Bot from Baidu are two other potential competitors to ChatGPT. Additionally, tools like Amazon Lex can be used to develop your own chatbots. There is also an open source language model called GPT-J, which is similar to OpenAI’s GPT-3. Notice that ChatGPT uses GPT-3.5 (used by the free product) and GPT-4 (used by the premium product). Microsoft’s search engine called Bing also has features based on GPT-4. Other chatbots available online include Perplexity, Jasper, Chatsonic (Writesonic), Replika, Tome, etc. However, many of these services are not free like ChatGPT.

Interestingly, some of these tools even provide the option to rewrite text to bypass AI content detection.

The second question is: What should you do when you have a strong affinity for a programming language that is not listed among the popular options for developing AI and machine learning applications? Fortunately, times have changed, and no programming language or development community can ignore the growing importance of AI. Almost every programming language has some features to support AI-based development. For instance, if you prefer JavaScript, a popular language for web development, there are now certain libraries and frameworks available to support AI and machine learning, such as TensorFlow.js, Brain.js, and ConvNetJS. These libraries enable developers to perform machine learning tasks directly in the browser, which is useful for creating interactive applications that rely on real-time predictions.

A few programming languages for AI

Now, let us explore some of the key programming languages that are used for developing AI. Prolog is a logic programming language that is well-suited for certain types of AI applications, such as expert systems and natural language processing. Released in 1971, Prolog is actively used today, though not at the same scale as many other programming languages discussed in this series. For example, one of the languages used to develop IBM Watson is Prolog. You can execute Prolog programs in your system by using a compiler called GNU Prolog. It can be installed in Ubuntu by using the command, ‘sudo apt install gprolog’. Prolog is worth considering as a potential candidate for AI development due to its unique programming paradigm. However, keep in mind that this language is used sporadically, and the chances of coming into contact with a professional Prolog programmer are slim.

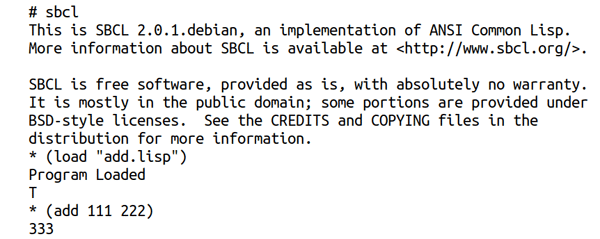

Lisp is another historically (being the second oldest surviving high-level programming language) and practically relevant programming language for AI development. Although Lisp is not as widely used as some other programming languages, it continues to have a dedicated community of developers who value its unique features and capabilities. Nowadays, Lisp has several dialects available, such as Clojure, Scheme, Racket, and Common Lisp. Common Lisp is presently one of the most popular dialects of Lisp, and SBCL (Steel Bank Common Lisp) is the most commonly used implementation of it. SBCL is an open source implementation known for its quick performance and high level of conformity to the Common Lisp standard. To install SBCL on Ubuntu, run the command, ‘sudo apt-get install sbcl’ in your terminal. Now, consider the Lisp program ‘add.lisp’, shown below, which adds two numbers. Figure 1 shows the execution of this Lisp program. Notice that executing the instruction ‘sbcl’ initiates the operation of the SBCL compiler.

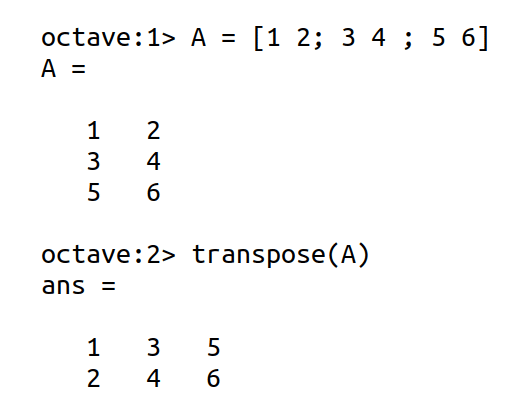

Let us now discuss GNU Octave, a free and open source programming language primarily used for scientific computing and numerical computation. Its compatibility with MATLAB, as well as its comprehensive set of tools, make it a powerful programming language for developing AI and machine learning-based applications. To install GNU Octave on Ubuntu, simply run the command ‘sudo snap install octave’ in your terminal, and to run the GNU Octave interpreter, execute the command ‘octave’. In Figure 3, a simple example of finding the transpose of a matrix using GNU Octave is shown. Note that matrix A has order 3×2 (3 rows and 2 columns) and therefore, the transpose of matrix A has order 2×3 (2 rows and 3 columns). It is worth noting that, unlike Scilab, this code (which is compatible with MATLAB) works perfectly fine with GNU Octave.

(format t “Program Loaded”) (defun add (a b) (+ a b))

Haskell, a true functional programming language, and Scala, which provides many functional programming capabilities, are also frequently utilised for creating AI and machine learning applications. Lisp, Haskell, and Scala are significant programming languages in the domain of AI because of the programming paradigm they support. Functional programming features are extremely beneficial when developing AI and machine learning applications. Although Python does support certain functional programming features, such as lambda functions, it is not enough, which underscores the critical importance of programming languages like Lisp, Haskell, and Scala.

Programming languages like C++ and Java are considered for developing AI when requirements like speed, low-level control, and scalability come into the picture. Since C++ and Java are quite well-known, let us move on to discussing other languages.

R is a programming language for statistical computing and is preferred over Python when strong statistical computing capabilities are required. For more details, I urge you to go through the ongoing series on R currently featured in Open Source For You.

In my opinion, a comprehensive discussion on the development of AI-based software should include references to proprietary programming languages and tools like MATLAB, Wolfram Mathematica, etc. However, I am aware that many advocates of free and open source software consider such tools as unacceptable. Personally, I align with the moderate faction of the free and open source software community, and do not entirely discourage the use of proprietary software. However, to avoid any controversy, I will talk about Scilab and GNU Octave, two programming languages that have the ability to mimic MATLAB effectively.

Before we proceed any further, I would like to introduce a textbook titled ‘Neural Data Science: A Primer with MATLAB and Python’ by Nylen and Wallisch. This textbook provides examples in both Python and MATLAB, which makes it easier to switch between the two programming languages. Furthermore, I have tested the code in this textbook using both Scilab and GNU Octave interpreters to ensure their conformity with MATLAB. These comparisons revealed that Scilab has lower syntactic compatibility with MATLAB than GNU Octave.

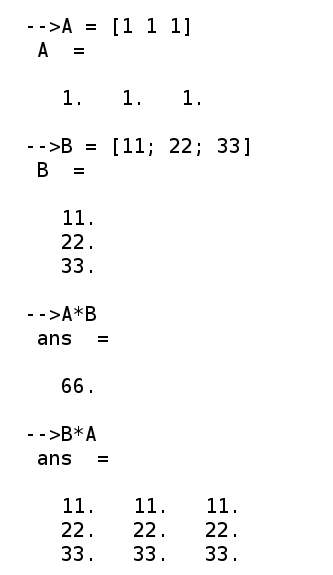

Now, let us discuss Scilab. It is a numerically-oriented programming language and a free and open source numerical computational package. Scilab is an excellent tool for developing AI and machine learning-based applications due to its ease of learning and rich set of libraries. To install Scilab on Ubuntu, run the command ‘sudo apt-get install scilab’ in your terminal, and execute the command ‘scilab’ to run the Scilab interpreter. Figure 2 shows a simple example of multiplying two matrices using Scilab. Note that matrix A is of order 1×3 (1 row and 3 columns) and matrix B is of order 3×1 (3 rows and 1 column). Therefore, the product matrix AB has an order of 1×1, with the single element being 66, while the product matrix BA has an order of 3×3. This is a valid MATLAB code as well, but even basic tasks expose the syntactic incompatibility of Scilab with MATLAB. For instance, the perfectly valid MATLAB code ‘C = transpose(B)’ produces the following error in Scilab: ‘Undefined variable: transpose’. As a result, potential users of Scilab should exercise extreme caution when using MATLAB code.

Let us now discuss GNU Octave, a free and open source programming language primarily used for scientific computing and numerical computation. Its compatibility with MATLAB, as well as its comprehensive set of tools, make it a powerful programming language for developing AI and machine learning-based applications. To install GNU Octave on Ubuntu, simply run the command ‘sudo snap install octave’ in your terminal, and to run the GNU Octave interpreter, execute the command ‘octave’. In Figure 3, a simple example of finding the transpose of a matrix using GNU Octave is shown. Note that matrix A has order 3×2 (3 rows and 2 columns) and therefore, the transpose of matrix A has order 2×3 (2 rows and 3 columns). It is worth noting that, unlike Scilab, this code (which is compatible with MATLAB) works perfectly fine with GNU Octave.

In fact, MATLAB-compatible code works almost flawlessly with GNU Octave, unlike Scilab. The syntactical differences between MATLAB and GNU Octave are relatively rare, but there are a few that might cause trouble. Figure 4 shows some minor syntactic differences between MATLAB (on the left side of the figure) and GNU Octave (on the right side of the figure). The first difference shown in Figure 4 is due to the different ways in which character strings and character arrays are treated by the two languages. The second difference is due to GNU Octave supporting the post-increment operator available in programming languages like C, C++, Java, etc. From Figure 4, it is clear that MATLAB does not support this operator, whereas its behaviour is similar in C, C++, Java, and GNU Octave. Keep in mind that these are not the only syntactical differences between MATLAB and GNU Octave. As the differences can be more subtle, GNU Octave users should be careful when using MATLAB code.

Introduction to Julia

Now, it is time to introduce Julia, a programming language that might pose the greatest threat to the dominance of Python in the development of AI and machine learning-based applications. Julia is a relatively new, high-level programming language designed for computational science. It was first released in 2012, and its features make it well-suited for developing AI and machine learning-based applications. Python and Julia can be compared using the analogy of a mobile phone camera and a digital camera. Python, being a widely-used programming language, is as versatile as a mobile phone and can be utilised for various applications, including AI-based development. In contrast, Julia is like a digital camera specialised in a particular task. Julia is designed for high-performance computing and numerical analysis. It is a relatively new language that has gained prominence in the scientific computing community due to its speed and efficiency. Julia’s syntax is somewhat similar to Python’s, but it is optimised for speed and efficiency, making it ideal for complex numerical computations and simulations. Thus, speed is one of the important reasons why you should prefer Julia over Python.

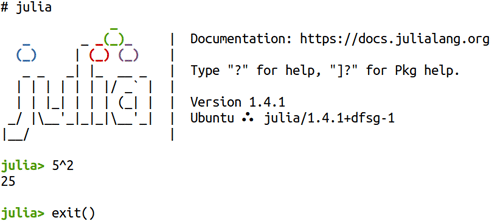

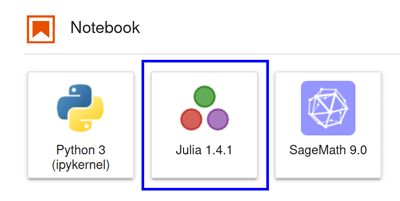

As Julia shows great potential as a programming language for AI in the future, let us delve into it further. To install Julia on Ubuntu, simply enter the command ‘sudo apt-get install julia’ in your terminal. Then use the command ‘julia’ to launch the Julia REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop), a command-line interface for working with Julia. To exit the Julia REPL, simply type ‘exit( )’ and press Enter. In Figure 5, you can see an example of the Julia REPL running a mathematical expression (5^2 = 25).

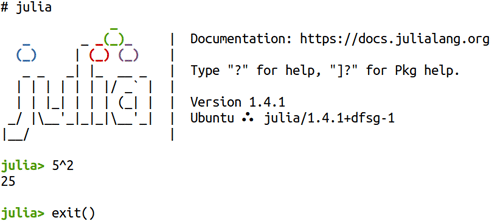

Now, let us write and execute a Julia program. Notice that Julia programs have a ‘.jl’ extension. Consider the Julia program called ‘pgm1.jl’ shown below, which generates a random array of integers, and calculates its mean and standard deviation.

using Statistics Arr = rand(1:100, 10) μ = mean(Arr) σ = std(Arr) println(“Array: $Arr”) println(“Mean: $μ”) println(“Standard Deviation: $σ”)

The line of code ‘using Statistics’ loads the package Statistics, which provides several statistical functions, including mean and standard deviation. The line of code ‘Arr = rand(1:100, 10)’ creates a one-dimensional array of length 10, filled with random integers between 1 and 100 (inclusive). The rest of the code calculates the mean and standard deviation of the array Arr, and prints the array Arr and the calculated results. Julia is a programming language intended for scientific computing and allows the use of mathematical symbols as variable names. For example, the above program uses the symbols μ and σ as variable names to store the mean and standard deviation, respectively. In the Julia REPL, you can get Unicode math symbols by typing the symbol names in LaTeX followed by typing the tab key. For example, the variable name μ can be generated by typing ‘\mu’ (LaTeX for μ) followed by the tab key in the Julia REPL. These types of variable names make the code more expressive, easier to read, and closer to the mathematical notation used in formulas and equations. The Julia program can be executed with the command ‘julia pgm1.jl’. Figure 6 shows the execution and the output of the Julia program pgm1.jl.

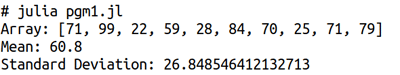

By now, we are quite familiar with JupyterLab and Jupyter Notebooks. One huge benefit of Julia is that it can be used with Jupyter Notebooks, allowing users to leverage the strengths of both technologies. IJulia is a package that enables the use of Julia within a Jupyter Notebook environment, making it easy to work with data, perform computations, and visualise results. In this series, we have already installed and used JupyterLab. Now, let us explore how IJulia can be installed and used as a kernel in Jupyter Notebooks. Once you have installed Julia, open the Julia REPL and enter the following two commands on the Julia prompt to add the IJulia package: ‘using Pkg’ and ‘Pkg.add(“IJulia”)’. The execution of these two commands will install the IJulia package on your system. Now, execute the command ‘Jupyter lab’ to access Julia in a Jupyter Notebook. Figure 7 shows the option to choose Julia (marked inside a blue box) as the kernel for a Jupyter Notebook. As mentioned earlier in this series, JupyterLab can support various kernels. As you can see, my system supports not only Julia but also Python and SageMath kernels.

Let us wrap up our discussion of Julia by comparing the execution speeds of Python and Julia.

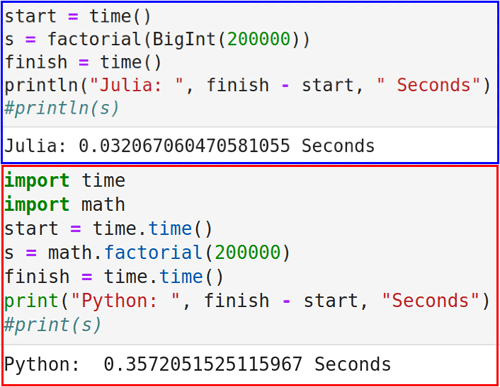

Figure 8 shows programs to find the factorial of the number 200000, using both Julia (shown at the top of the figure) and Python (shown at the bottom of the figure). Just in case you forgot what a factorial is, the factorial of 5 (denoted as 5!) is 120 (5x4x3x2x1). The programs are straightforward because both Julia and Python have a function called factorial( ) to find the factorial of a number. I commented out the line of code to print the answer obtained because the final answer has nearly a million digits (973,351 to be exact), which would require 235 A4-size pages to print. Figure 8 also shows the amount of time that the Julia and Python programs took to complete the calculation. It is evident that Python took ten times longer than Julia. While there are strategies to optimise the code, this is the most apparent code that comes to the mind of most programmers, and Julia is the undisputed victor here.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasise the speed of Julia — it produced a number with almost a million digits in less than 33 milliseconds on my laptop (which has modest specifications).

Let us now pause for a moment to consider the remarkable advances in computing power and scientific progress over the last century. Although it is a bit saddening that we can only imagine the technology that will exist 100 years hence, it brings us peace and happiness to know that our children will have a brighter future due to the rapid progress in science and technology.

A quick recap

Now, let us briefly go over the topics covered in this series, along with some key topics that were either left out or given only brief coverage. In this series, I attempted to introduce maths, particularly linear algebra and probability, as needed. However, it is important to note that our discussions were not highly formal or extensive. I want to emphasise once again that understanding maths is crucial for mastering the techniques required for developing AI-based solutions, without which you will be stuck copying code from Stack Overflow forever. To gain a thorough and formal understanding of these topics, I recommend the books ‘Linear Algebra Done Right’ by Sheldon Axler and ‘A First Course in Probability’ by Sheldon Ross. Please keep in mind that these are my personal recommendations, and there are many other textbooks available that cover these subjects in a way that may be more suitable for you.

Apart from the mathematical aspects, we have also done a lot of coding as part of the series. We did not approach the series in a programming language-agnostic way; rather, we relied mostly on Python for coding. While programming with Python, we used tools like JupyterLab and Anaconda Navigator. We covered almost all the major Python libraries and packages, such as TensorFlow, Keras, PyTorch, scikit-learn, Pandas, OpenCV, Matplotlib, etc, which are used for developing AI and machine learning-based applications. Identifying and utilising relevant Python libraries is crucial due to the vast number of options available, and I hope you will give it serious thought. In every article in this series, we also discussed the theoretical aspects of AI and machine learning. I hope that you will continue to update yourselves with the most recent developments in the AI industry.

Let us now examine the various AI and machine learning paradigms that we explored throughout this series. We provided comprehensive coverage of supervised learning and delved into the specifics of classification and regression using different Python libraries. However, to truly enhance your understanding of supervised learning, it is essential to work through more examples. While support vector machines (SVMs) are a critical component of supervised learning, our coverage of them was minimal, and we did not engage in any theoretical discussion regarding them. As a result, I highly recommend dedicating time to master both the theory and application of SVMs.

Our coverage of unsupervised learning was relatively limited compared to supervised learning. We presented an example of how clustering could be implemented, but there is still much more to learn about unsupervised learning, even with clustering. Additionally, we entirely omitted the topic of dimensionality reduction, a crucial aspect of unsupervised learning. By doing so, we disregarded techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) and independent component analysis (ICA). Therefore, I suggest taking the time to study these techniques in-depth.

We briefly touched on the two lesser-known paradigms of machine learning, semi-supervised learning and reinforcement learning. Acquiring knowledge in these areas could prove beneficial in the long run for your journey through AI and machine learning. Neural networks are the fundamental building blocks for AI-based applications. Learning the specifics of neural networks formally, rather than informally as we treated them, could have a tremendous impact on your understanding of AI.

As we come to the end of this 12-part series on AI, I am reminded of a quote by the famous poet W.H. Auden, “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.” Looking back, I feel the same way about this series. There were many things I could have done differently, such as adding or excluding topics or improving the presentation. However, I am happy with the journey we have taken, which I feel has served its purpose of introducing eager learners to the field of AI. Although I may have deviated from the original plan on occasions, I have remained faithful to the goal of introducing the maths and programming behind AI-based applications, albeit less formally than originally intended. Indeed, what sets this series apart, in my opinion, is our unique approach of blending the theoretical, mathematical, and programming aspects of AI.

During our one-year journey through AI, we witnessed a growing interest in the subject from the general public, which reached its peak with the introduction of ChatGPT. As an example of this, ChatGPT was featured on the cover page of the March 2023 issue of Frontline magazine. I cannot recall any other software or tool making such headlines in such a short amount of time. It would not be surprising if ChatGPT is chosen as Time magazine’s ‘Person of the Year’ for 2023, much like ‘The Computer’ was chosen in 1982.

As we end this series at a time when there is a major breakthrough in the field of AI, I offer these parting words of advice: formally learn the mathematical concepts introduced in this series, delve deeper into the Python libraries, and start developing a project that interests you which is of intermediate size and complexity, in order to practice the skillsets you have gained through this series.

I end with the hope that the series has been beneficial to you, and I extend my best wishes for an enjoyable and thrilling journey in the domain of AI.