In the last article in this SageMath series (published in the March 2025 issue of Open Source For You), we concluded our discussion on symmetric-key encryption. As promised, this article will focus on public-key cryptography (PKC). However, before diving into that, we will briefly examine some recent developments in the field of quantum computing. We will also introduce the concept of cryptanalysis to understand how these emerging trends could have potentially catastrophic implications for cybersecurity.

A few months ago, I had a déjà vu moment when Microsoft announced the development of a quantum computing chip. It reminded me of an earlier experience: while I was writing a series of articles on artificial intelligence for OSFY, something historic happened. On 30th November 2022, ChatGPT was made publicly available. I started experimenting with it immediately and managed to publish an article featuring ChatGPT in the January 2023 issue of OSFY. I still proudly claim — though I have no concrete proof — that this was the first mention of ChatGPT in a printed magazine in India.

Fast forward to the present: I am now writing a series on SageMath and currently focusing on cybersecurity. And right on cue, along comes an invention that could potentially upend many foundational aspects of cybersecurity as we know it.

Majorana 1: A milestone in quantum computing?

Microsoft’s new quantum chip, named Majorana 1, is being hailed as a breakthrough. The chip is said to support quantum superposition and entanglement at room temperature, making room-temperature qubits a practical reality — something that, until now, seemed decades away.

The chip is named after Ettore Majorana, a brilliant Italian physicist often described as “the next Einstein.” Majorana mysteriously disappeared in 1938 at the age of 31, and his legacy includes the theoretical concept of Majorana fermions — particles that are their own antiparticles. Microsoft’s approach to topological quantum computing is believed to leverage ideas inspired by these fermions, which are thought to provide enhanced stability against quantum decoherence — one of the key challenges in building scalable quantum systems.

However, much like the elusive scientist himself, the Majorana 1 chip has sparked a fair amount of scepticism in the scientific community. The claims are bold, and peer-reviewed validation is still awaited. Still, if the results hold up, this could dramatically accelerate the timeline for practical quantum computing — from centuries or decades down to just a few years.

Why this matters for cybersecurity — and for SageMath users

Here is where things get especially relevant to our discussion on cybersecurity using SageMath. Quantum computing presents a serious threat to many existing public-key cryptographic systems, especially those based on RSA and ECC. These systems rely on the computational hardness of problems like integer factorization and discrete logarithms — problems that quantum algorithms like Shor’s algorithm can solve exponentially faster than classical algorithms. This means that once practical quantum computers become available, much of today’s encryption could be broken in a matter of seconds — making sensitive data, secure communication, and digital authentication systems vulnerable to quantum attacks.

In this article, we will begin exploring cryptanalysis. With quantum computing on the horizon, cryptanalysis — the science of breaking codes — could become orders of magnitude more powerful than anything currently possible, outpacing even the most advanced supercomputers. So, as we dive into these cryptographic algorithms and their SageMath implementations, it is essential to keep one eye on the future — a future that might arrive much sooner than expected.

Crytptanalysis

Before we delve into cryptanalysis, it is important to first understand the concept of a brute-force attack — a method where every possible key is systematically tried until the correct one is found. On classical computers (the computers we use now), brute-force attacks become practically infeasible as the key size increases, thanks to the exponential growth in the number of possible keys. However, quantum computers can perform certain types of computations much faster than classical ones. This raises the concern that quantum computing systems could significantly accelerate brute-force attacks, reducing the time required to break encryption that is currently considered secure.

Now, let us examine how quantum computing impacts brute-force attacks and cryptanalysis. One of the key quantum algorithms relevant here is Grover’s algorithm, which provides a significant speedup for brute-force search problems. While classical algorithms require O(N) time to search an unstructured space of size N, Grover’s algorithm can accomplish the same task in O(√N) time. This means that a 128-bit key, which currently offers strong security, would provide only 64-bit effective security against an adversary with access to a quantum computer. In other words, quantum computers could weaken symmetric-key encryption, even if they don’t break it entirely. It is important to understand that the main threat quantum computing poses to symmetric-key encryption lies in its general computational speedup, rather than in any specific vulnerability in the encryption algorithms themselves. With that understanding, let us now explore a few examples of cryptanalysis applied to some widely used symmetric-key encryption schemes.

In the field of cryptanalysis, several techniques are used to evaluate and potentially break encryption schemes. These include ciphertext-only attacks, where the attacker has access only to encrypted messages; known-plaintext attacks, where some pairs of plaintext and ciphertext are known; chosen-plaintext attacks, where the attacker can encrypt messages of their choosing; and chosen-ciphertext attacks, where the attacker can decrypt selected ciphertexts without knowing the key.

In a known-plaintext attack (KPA), the attacker uses known pairs of plaintext and corresponding ciphertext to infer the key or decrypt other ciphertexts. This approach is more powerful than ciphertext-only attacks and was used successfully against classical ciphers like the Vigenère cipher. A chosen-plaintext attack (CPA) is even stronger — here, the attacker can choose arbitrary plaintexts and observe their corresponding ciphertexts. This helps reveal patterns in the encryption process and is commonly used to evaluate modern block and stream ciphers. In a chosen-ciphertext attack (CCA), the attacker can select ciphertexts and obtain their decrypted plaintexts. All these attack models—ciphertext-only, known-plaintext, chosen-plaintext, and chosen-ciphertext—will become significantly more potent with the advent of quantum computers.

Now, consider the SageMath program named ‘kpa28.sage’ shown below (line numbers are included for clarity), which implements a known-plaintext attack (KPA) on the Vigenère cipher. Recall that we discussed the Vigenère cipher in detail in the seventh article in this series (published in the November 2024 issue of OSFY).

1. alphabet = “ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ”

2. letter_to_index = {c: i for i, c in enumerate(alphabet)}

3. index_to_letter = {i: c for i, c in enumerate(alphabet)}

4. def vigenere_encrypt(plaintext, key):

5. ciphertext = “”

6. for i, c in enumerate(plaintext):

7. pi = letter_to_index[c]

8. ki = letter_to_index[key[i % len(key)]]

9. ci = (pi + ki) % 26

10. ciphertext += index_to_letter[ci]

11. return ciphertext

12. plaintext = “HELLOOPENSOURCEFORYOU”

13. key = “DEEPU”

14. ciphertext = vigenere_encrypt(plaintext, key)

15. print(“Ciphertext:”, ciphertext)

16. recovered_key = “”

17. key_length = len(key)

18. for i in range(key_length):

19. pi = letter_to_index[plaintext[i]]

20. ci = letter_to_index[ciphertext[i]]

21. ki = (ci - pi) % 26

22. recovered_key += index_to_letter[ki]

23. print(“Recovered Key:”, recovered_key)

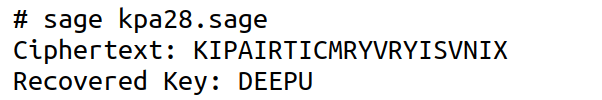

Upon executing the program ‘kpa28.sage’, the output shown in Figure 1 is obtained. As can be verified, the secret key is successfully recovered.

Now, let us go through the code line by line to understand how it works. Lines 1 to 11 implement the Vigenère cipher encryption. Recall that this code is already known to us. Line 12 defines the plaintext message to be encrypted as ‘HELLOOPENSOURCEFORYOU’. Line 13 defines the encryption key as ‘DEEPU’. Line 14 calls the function vigenere_encrypt( ) (defined earlier) to encrypt the plaintext using the key ‘DEEPU’. Line 15 prints the ciphertext generated from the previous step. Line 16 initialises an empty string named recovered_key. Line 17 defines the length of the original key (which is 5, since ‘DEEPU’ has 5 characters) and stores it in a variable named key_length. Recall that the key length in the Vigenère cipher can be determined using the Kasiski examination, as discussed in the article covering the Vigenère cipher. The loop in lines 18 to 22 recovers the original key using the known-plaintext attack method. The variable pi has the index of the ith plaintext character (for example, ‘H’ → 7). The variable ci has the index of the ith ciphertext character. The variable ki has the index of the ith key character, recovered by reversing the encryption formula (Line 21). Finally, Line 23 prints the recovered key.

Now, consider the SageMath program named ‘cpa29.sage’ shown below, which implements a chosen-plaintext attack on the Vigenère cipher. To enable Vigenère cipher encryption, lines 1 to 11 of the program ‘kpa28.sage’ should be added at the beginning of the program ‘cpa29.sage’.

chosen_plaintext = “AAAAA” ciphertext = vigenere_encrypt(chosen_plaintext, secret_key) print(“Ciphertext received:”, ciphertext) recovered_key = “” for i in range(len(chosen_plaintext)): pi = letter_to_index[chosen_plaintext[i]] ci = letter_to_index[ciphertext[i]] ki = (ci - pi) % 26 recovered_key += index_to_letter[ki] print(“Recovered Key:”, recovered_key)

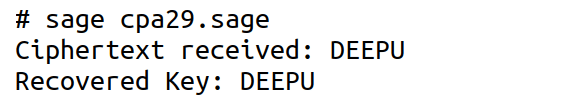

Upon executing the program ‘cpa29.sage’, the output shown in Figure 2 is obtained. As can be verified, the secret key is successfully recovered.

Now, let us understand how the program works. The attacker selects the chosen plaintext ‘AAAAA’, which is then encrypted using the secret key via the function vigenere_encrypt( ). Since the letter ‘A’ corresponds to index 0, each character in the resulting ciphertext directly reveals the shift applied at that position—effectively exposing the corresponding key character. As a result, the program successfully reconstructs the original key by leveraging the predictable behaviour of the Vigenère encryption when a known input is used.

Once we are familiar with the chosen-plaintext attack, it becomes easier to understand the chosen-ciphertext attack, as both involve controlled access to the encryption or decryption process to recover the key or plaintext. In a chosen-plaintext attack, submitting a plaintext like ‘AAAAA’ causes the ciphertext to directly reflect the key, since the shift applied to each ‘A’ corresponds to the key character. Similarly, in a chosen-ciphertext attack, submitting a ciphertext like ‘AAAAA’ and observing its decrypted plaintext allows the attacker to compute the key by reversing the shift. Although one starts with plaintext and the other with ciphertext, both attacks exploit the regular, repeating structure of the Vigenère cipher to uncover the key with minimal effort.

The examples discussed here are intentionally simple, but the same underlying principles can be applied to attack stronger, widely used ciphers such as 3DES, AES, and others. Moreover, beyond the attacks we have already mentioned, there are more advanced and potent techniques—such as the meet-in-the-middle attack, differential cryptanalysis, and linear cryptanalysis. The threat posed by all these attacks becomes significantly more serious with the computational speedup offered by quantum computers, potentially compromising encryption schemes once considered secure. Thus, quantum computers are expected to create a surge in demand for skilled computer professionals—similar to the Y2K era, but on a much larger and more complex scale.

Public key cryptography

Now, it is time to uncover how public-key cryptography (PKC) works. PKC is often seen as counter-intuitive because it openly shares what seems to be half of the key—the public key—yet still maintains strong security. Traditionally, secrecy in cryptography depended on keeping the entire key hidden, as seen in symmetric encryption. However, in public-key cryptography, one key (the public key) is made available to everyone, while the other (the private key) remains secret. The surprising strength of this system lies in the use of one-way mathematical functions, such as factoring large numbers or solving discrete logarithms, which are easy to compute in one direction but practically impossible to reverse without the private key. Despite appearing to ‘leak’ half of the key, the security holds because knowing the public key does not enable an attacker to efficiently derive the private key or decrypt messages.

Diffie-Hellman key exchange (DH), introduced in 1976, was groundbreaking as the first practical method for securely exchanging cryptographic keys over an insecure channel. While DH itself is not an encryption scheme, it established the fundamental idea of using modular arithmetic and hard mathematical problems (like discrete logarithms) for secure communication. The success of DH in demonstrating the feasibility of public-key cryptography directly paved the way for RSA and its widespread adoption. RSA was developed by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman in 1977 at MIT, and the algorithm is named after their initials. RSA built upon similar mathematical principles, particularly modular exponentiation, but instead of key exchange, it provided a complete encryption system using asymmetric cryptography.

Since RSA can be somewhat counter-intuitive and difficult to grasp at first, this article will focus on a simplified, toy model known as Kid-RSA (KRSA), which captures the core ideas of RSA in an easier-to-understand form. KRSA is a simplified, insecure public-key cipher published in 1997, designed for educational purposes. Cybersecurity researchers often feel that learning KRSA gives insight into RSA and other public-key ciphers, analogous to simplified data encryption standard (S-DES).

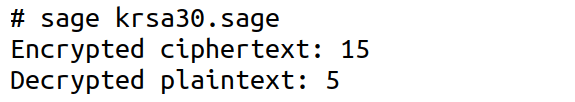

Now, consider the SageMath program named ‘krsa30.sage’ shown below, which implements the KRSA encryption scheme. The program demonstrates the encryption and decryption of a single number, 15. However, it is important to note that encoding schemes like ASCII or Unicode represent characters as numbers. Therefore, with slight modifications, this program can be extended to encrypt entire messages by processing their numerical representations.

a = 3 n = 17 b = inverse_mod(a, n) M = 5 C = (M * a) % n print(“Encrypted ciphertext:”, C) decrypted = (C * b) % n print(“Decrypted plaintext:”, decrypted)

Now, let us understand how the program works. The program uses modular multiplication over a prime modulus to implement KRSA. The encryption key a is set to 3, and the modulus n is chosen as 17 (a prime number to ensure the existence of modular inverses). The decryption key b is computed as the modular inverse of a modulo n. A plaintext value M = 5 is encrypted as C = (M * a) % n, and the ciphertext is then decrypted using decrypted = (C * b) % n. The decryption process successfully recovers the original plaintext value, demonstrating the reversibility of the encryption when working in a finite field defined by a prime modulus.

In this example, the public key consists of the pair (a,n), where a=3 is the encryption multiplier and n=17 is the prime modulus. The private key is derived by computing the modular inverse of a modulo n, resulting in b=inverse_mod(a,n), which equals 6. Therefore, the private key is the pair (b,n), which in this case is (6,17).

Now, let us consider a scenario where Alice wants to send a message to Bob. (Recall that Alice and Bob are classical characters commonly used in cybersecurity textbooks and examples.) To send her message securely, Alice uses Bob’s public key, which in this case is (3,17), to encrypt the plaintext. She then sends the resulting ciphertext to Bob. Since only Bob knows the private key (6,17), he alone can decrypt the ciphertext and retrieve the original message.

It is important to note that while anyone can encrypt messages using Bob’s public key, only Bob can decrypt them using his private key. This eliminates the need to exchange a secret key over a potentially insecure channel — a major challenge in symmetric-key encryption. In fact, Bob can even publish his public key openly, for example on social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, without compromising the security of the communication.

Upon executing the program ‘krsa30.sage’, the output shown in Figure 3 is obtained. As shown, the original plaintext value of 5 is successfully recovered during decryption.

Now, it is time to wrap up our discussion. In this article, we explored how cybersecurity could be significantly impacted in the near future by advancements in quantum computing. We also introduced the concept of cryptanalysis and concluded with the basics of public-key cryptography through a simplified model called Kid-RSA (KRSA). In the next article in this series, we will continue our exploration of public-key cryptography, with a special focus on understanding and implementing RSA.