Modern Linux distributions prefer the UEFI booting process over legacy BIOS booting. Let’s find out why.

Every time we press the power button on a computer, a complex chain of events begins—one that ends with our Linux desktop or server environment becoming fully functional. This process, called booting, involves multiple layers of interaction between firmware, storage devices, bootloaders, and the kernel.

For decades, computers relied on the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) firmware, which operated in a simple but rigid way. However, as hardware evolved, BIOS showed its limitations: inability to handle disks larger than 2TB, restricted partitioning, and limited extensibility.

UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) was introduced to overcome these challenges. It modernised the boot process with modular phases, support for larger disks, and features like Secure Boot.

Understanding the boot process

Before diving into BIOS and UEFI, it’s important to outline the general flow of a boot sequence.

- Power-on and firmware initialisation: The firmware (BIOS or UEFI) initialises hardware components and determines the boot device.

- Bootloader loading: A small program (bootloader) is loaded from the disk into the memory of the computer.

- Kernel loading: The bootloader loads the Linux kernel and initial RAM filesystem, which is called initramfs.

- Kernel initialisation: The kernel initialises device drivers, mounts the root filesystem, and launches systemd or init, which brings up user space.

Legacy BIOS booting

Let’s first explore the legacy BIOS booting process.

Power-on and CPU reset

When you press the power button, a reset signal is sent from the clock generator chip on the motherboard to the CPU reset pin. The signal is held high for a few clock cycles (depending on CPU type) and then goes low, which resets the CPU. On reset:

- CPU registers are initialised to a predetermined state.

- The instruction pointer (IP) is set to the reset vector address (a 20-bit address).

- This reset vector points to the start of the BIOS firmware.

At this stage, the CPU begins fetching and executing instructions directly from the BIOS chip (ROM/flash) without needing to copy them to RAM (execution-in-place).

BIOS execution and stages

BIOS is a collection of low-level programs stored in a ROM/flash chip on the motherboard. It has three internal roles.

- Startup routines: Initialising CPU, memory, chipset, and peripheral devices.

- Service handling routines: Software interrupts (INT calls) for OS and bootloader.

- Hardware interrupt handling: Basic interrupt handling for keyboard, timers, etc.

POST (Power-On Self-Test)

The first program BIOS runs is POST, which checks:

- CPU registers

- BIOS routines integrity

- Keyboard

- CMOS RAM

- Other essential hardware.

Once complete, BIOS copies itself from ROM to RAM (shadowing) for faster execution and then disables the ROM mapping. After POST, BIOS executes INT 19h, the bootstrap loader service. This routine begins the OS boot process.

Warm vs cold boot

BIOS checks the memory location 0x0472 in the BIOS data area.

- If value = 1234h → Warm boot (restart).

- Otherwise → Cold boot (fresh power-on).

The CMOS RAM contains a shutdown status byte that also helps BIOS determine the reset type.

Boot device selection

BIOS checks devices (HDD, USB, CD, etc) based on the boot order stored in CMOS.

For each device:

- It reads the first sector (512 bytes) = MBR (Master Boot Record).

- If the last two bytes = 0xAA55 → MBR is valid.

- If invalid → BIOS continues to the next boot device.

If no valid boot device is found, BIOS executes INT 18h (no boot device found error).

Master Boot Record (MBR)

Once a valid MBR is found, BIOS loads it into memory at address 0x7C00.

The MBR structure is:

- 446 bytes – Bootloader code

- 64 bytes – Partition table (4 entries × 16 bytes)

- 2 bytes – Boot signature (0xAA55)

Note that MBR has no backup and it can only describe four primary partitions (limitation).

Partition Boot Record (PBR/VBR)

MBR boot code checks the partition table for an active partition (bootable flag = 0x80).

It loads the first sector of the active partition (the Volume Boot Record) into memory at 0x7C00. VBR contains filesystem-specific boot code and metadata:

- Sector size, sectors per cluster

- Partition type (FAT, NTFS, ext, etc)

The VBR boot code loads the second-stage bootloader (GRUB, LILO, etc).

Bootloader stages

The bootloader is executed in multiple phases.

- Zero stage bootloader: Startup code inside BIOS.

- First stage bootloader (MBR + VBR code): Minimal initialisation, loads second stage.

- Second stage bootloader (GRUB/LILO): Provides full boot menu, loads the OS kernel.

GRUB (Grand Unified Bootloader)

GRUB is the most common Linux bootloader, located typically in /boot/grub/grub.conf or /boot/grub2/grub.cfg. Its responsibilities are:

- Display boot menu (Linux, recovery mode, dual-boot OS).

- Load Linux kernel (vmlinuz) into memory.

- Load initramfs/initrd (temporary root filesystem with drivers).

- Pass kernel parameters (e.g., root filesystem location).

Kernel loading

GRUB hands control to the Linux kernel. Kernel tasks are:

- Initialise CPU and memory management.

- Load device drivers from initramfs.

- Mount the real root filesystem.

Transition to user space

After kernel initialisation, the first user space process (PID 1) is launched:

- Old Linux → /sbin/init.

- Modern Linux → systemd.

- The responsibilities are:

- Mount additional filesystems.

- Start essential daemons (networking, logging, etc).

- Bring system to the configured run level/target (multi-user, graphical).

Finally, the login prompt (CLI) or display manager (GUI) appears. At this point, Linux is fully booted and ready for user interaction.

BIOS booting is sequential and limited (MBR, 2TB disk limit, 16-bit real mode). It relies heavily on GRUB/LILO for loading Linux. Modern systems mostly use UEFI, but understanding BIOS boot flow is essential for legacy hardware and OS troubleshooting.

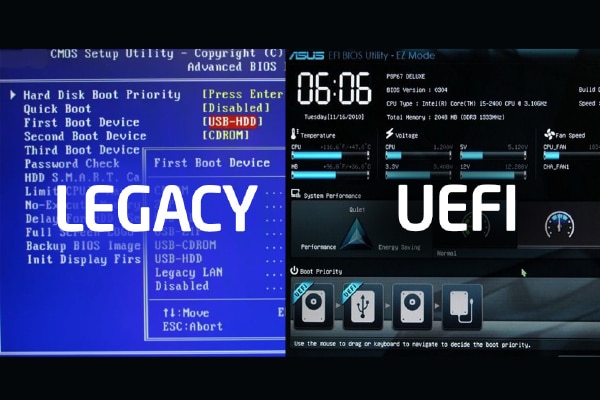

BIOS vs UEFI

| Feature | BIOS | UEFI |

| Initialisation | POST (monolithic) | Modular phases (SEC, PEI, DXE, BDS) |

| Execution mode | 16-bit real mode | 32-bit or 64-bit protected/long mode |

| Storage scheme | MBR (2 TB disk limit) | GPT (supports huge disks, >2 TB) |

| Bootloader | First 512 bytes (MBR) | EFI System Partition (ESP, FAT32) |

| Drivers | BIOS-internal only | Modular UEFI drivers loaded dynamically |

| Security | None | Secure Boot, TPM, Boot Guard supported |

| Flexibility | Limited | Extensible (protocols, drivers, apps) |

UEFI booting

UEFI booting begins at system power-on, where the firmware initialises hardware and performs integrity checks. Unlike legacy BIOS, which relies on the Master Boot Record (MBR), UEFI loads the operating system’s bootloader directly from the EFI System Partition (ESP). This partition is typically formatted as FAT32 and works with modern partitioning schemes such as GPT, supporting larger disks and more partitions.

As systems evolved, BIOS’s 16-bit real-mode execution and MBR limitations became a bottleneck. UEFI was designed to:

- Support larger disks (>2TB).

- Provide a modular driver model.

- Include secure booting capabilities.

- Be extensible with pre-OS applications and networking.

Here’s how it works.

Power-on and reset

When the power button is pressed:

- PSU (power supply unit) receives signal.

- Performs PWR_OK check → ensures stable voltages.

- Sends Power Good signal to CPU + motherboard.

- In the CPU reset state:

- CPU comes out of reset, ready to fetch its first instruction.

- Starts in real mode (16-bit).

- Backward compatibility with 8086 code.

- IP (Instruction Pointer) set to reset vector:

- CS:IP → 0xFFFF:0xFFF0 → Physical address 0xFFFFFFF0.

- Maps to firmware ROM on motherboard.

- Firmware places a jump instruction → enters SEC phase.

SEC phase (Security/Initialisation)

This phase begins with the CPU state setup as follows:

- Clear leftover reset state.

- Disable interrupts.

- Set up a temporary stack (in registers or cache-as-RAM).

Microcode updates come next. CPU microcode fixes are applied from firmware blobs.

Platform security is ensured by verifying digital signatures of the next firmware stage (if Secure Boot, Boot Guard, TPM enabled). Establishing Root of Trust ensures execution of trusted code only.

Memory unavailable problem indicates:

- DRAM not yet initialised.

- Use Cache-as-RAM (CAR): CPU cache configured to act as temporary RAM.

- Stack + variables stored in cache.

- To locate next stage:

- SEC prepares handoff structure (CPU state, basic platform information).

- Transfers control to PEI phase.

PEI phase (Pre-EFI initialisation)

This phase is run by:

- PEI Core = supervisor.

- PEIMs (Pre-EFI Modules) = workers for CPU, DRAM, chipset.

- Key actions are:

- Run on Cache-as-RAM.

- Initialise DRAM:

- Reads DIMM SPD information.

- Sets up memory controller (timing, training).

- Switches stack + data from CAR → real DRAM.

- Initialise essential chipset parts:

- Clock generators, PCI root basics, debug console

- Build HOBs (Hand-Off Blocks):

- Memory map

- CPU + firmware information

- Firmware volume locations

In the handoff, PEI passes control + HOB list to DXE Core.

DXE (Driver Execution Environment) phase

This phase is run by:

- DXE core = central coordinator

- DXE drivers = handle hardware devices

Key actions are:

- Load drivers

- Drivers from firmware volumes (FVs) loaded into DRAM.

- Device discovery

- PCI, USB, SATA, GPU, network initialised.

- Console devices (keyboard, graphics, serial) ready.

- Handle database

- Devices are represented by Handles.

- Handles are linked to protocols (APIs by GUIDs).

- Ex: EFI_BLOCK_IO_PROTOCOL, EFI_GRAPHICS_OUTPUT_PROTOCOL.

- Boot services

- Memory allocation

- Image loading

- Protocol lookup

- Event + timer services

- Console setup

- Enables BIOS/UEFI setup UI (keyboard + graphics output).

In the handoff, after all drivers are initialised, boot manager and boot device selection (BDS) are invoked.

BDS phase (Boot device selection/Boot manager)

The boot manager (part of DXE) runs this phase. Key actions are:

- Read boot configuration from NVRAM variables:

- BootOrder, Boot####.

- Select boot device (disk, USB, PXE, etc).

- Locate OS loader in EFI System Partition (ESP):

- bootmgfw.efi (Windows)

- grubx64.efi (Linux)

- Secure Boot verification (if enabled).

- Load + execute OS loader as a UEFI application.

OS loader execution

Examples are:

- Windows → bootmgfw.efi

- Linux → grubx64.efi / shimx64.efi

Key actions are:

- Use UEFI Boot Services to:

- Read kernel + initramfs from disk.

- Access graphics/network for menus.

- Load kernel image + initramfs into DRAM.

- Call GetMemoryMap() → snapshot of memory layout.

- Call ExitBootServices() → firmware boot services shut down.

OS kernel takes control

In the handoff, the loader jumps to the kernel entry point. The CPU is now fully under kernel control.

Kernel initialisation is as follows:

- Setup: CPU mode, paging, IDT, memory management.

- Initialise drivers + devices.

- Start scheduler, kernel threads.

- Mount initramfs, then switch to real root FS.

UEFI runtime services still available are:

- GetTime(), SetTime()

- GetVariable(), SetVariable() (NVRAM)

- ResetSystem()

Entering user space

Kernel spawns init process (PID 1):

- Linux → /sbin/init (systemd/upstart).

- Windows → smss.exe.

- Init responsibilities are:

- Mount filesystems.

- Start background services.

- Launch login services (CLI/GUI).

User space is now fully alive. The user sees the login prompt/desktop. OS operation is normal from here.

The UEFI boot process is a modern, modular, and secure replacement for the legacy BIOS booting sequence. BIOS is simple but limited — it runs in 16-bit real mode, uses MBR, and has no built-in security. UEFI brings flexibility and power. It runs in 32/64-bit mode, uses a phased approach (SEC → PEI → DXE → BDS), and supports GPT disks with larger storage. It offers standardised services (boot services and runtime services), and strong security (Secure Boot, TPM).

Ultimately, UEFI bridges the gap between firmware and OS. It securely initialises hardware, loads drivers, hands off to the OS loader, and fades into the background while leaving behind only minimal runtime services.