Knowledge of Docker is a prerequisite for building scalable and portable applications in the cloud era. Let’s explore what Docker is, how it works, why it is so popular, and when you should avoid using it.

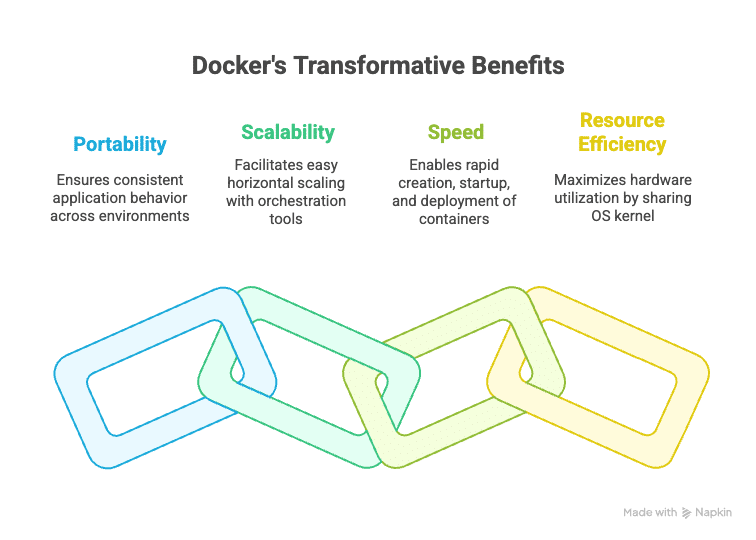

Agility, scalability, and consistency of software systems are musts in the AI world. As these systems grow in complexity, there is more pressure on IT teams to produce, test, and implement applications quickly without compromising on their reliability or performance. Traditional deployment methods, such as virtual machines or manual configuration, fall short in performance today. Docker’s entry into this field has changed the face of software development and deployment.

Docker is an open source platform developed to help automate the deployment of applications inside lightweight, portable-running containers. These containers house anything the application needs to run — code, runtime, libraries, and system tools. It offers a sort of perfect packaging where everything is in an isolated environment from the host system. In this way, it eliminates the classic “it works on my machine” problem and ensures the application behaviour remains consistent, right from the developer’s machine to the cloud-based production environment.

Containerisation has been around for a while; however, Docker has made it simpler, faster, and developer friendly. It rose to stardom in 2013 and is today embedded in modern workflows, especially in areas such as:

DevOps: Docker supports smoother CI/CD pipelines and infrastructure automation.

Microservices: Services may be independently developed, deployed, and scaled using it.

Cloud computing: Containers are the best way to deploy freely scalable applications in public, private, or hybrid cloud settings.

Testing and QA: Easily duplicate an environment in which automated tests can be performed or in which production can be simulated.

In the time that Docker has been around, its ecosystem has grown rapidly and now includes tools like Docker Compose for multi-container applications, Docker Hub for image sharing, and integrations with orchestrators such as Kubernetes for large-scale deployments.

What is Docker?

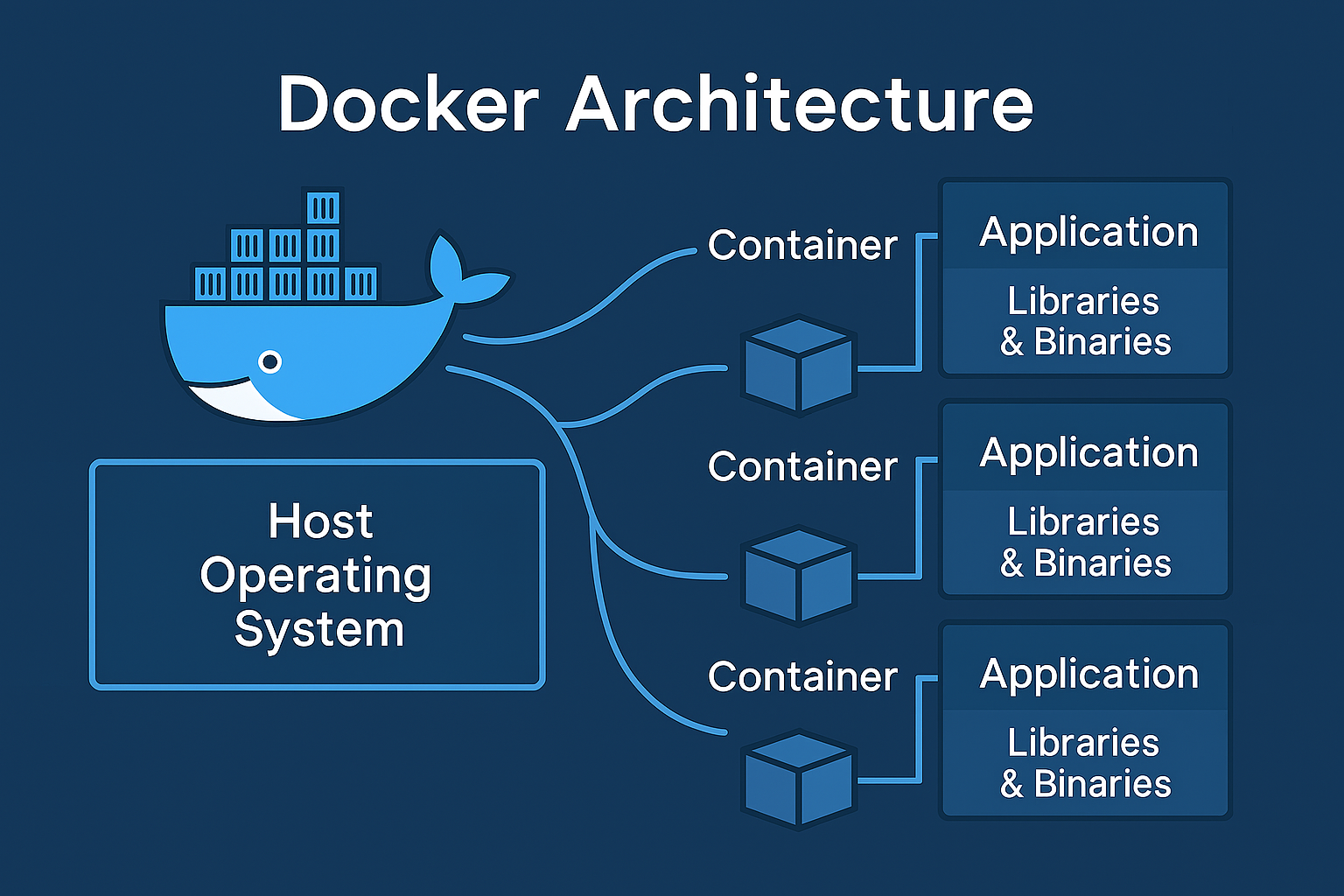

At its core, Docker is an open source platform that enables developers to create, package, and distribute applications as containers. Being a container means it is a light, standalone executable software package inclusive of everything required to run a piece of software: the application code, runtime, systems tools, libraries, and settings.

Docker eases the delivery pipeline by ensuring the application runs without hindrance on any environment, be it the left shutdown on your laptop or a cloud production instance. With Docker, application developers can simply concentrate on writing code and forget about the environment setup while operations teams are assured of deployments that are predictable and repeatable.

Docker uses an engine-client-server model, wherein the Docker Engine is responsible for creating and running containers. A Docker CLI can be used to issue Docker commands from a command-line terminal on a given platform, and Docker Hub or other registries store and share available container images.

Containers vs virtual machines

|

Feature |

Containers (Docker) |

Virtual machines (VMs) |

|

Architecture |

Share the host OS kernel |

Run a full guest OS on top of a hypervisor |

|

Size |

Lightweight (typically in MBs) |

Heavy (typically in GBs) |

|

Startup time |

Very fast (seconds or less) |

Slower (minutes) |

|

Isolation |

Process-level isolation (shared kernel) |

Stronger, full OS-level isolation |

|

Resource usage |

Efficient — uses fewer resources |

High — each VM duplicates OS resources |

|

Performance |

Near-native performance |

Slightly lower due to virtualization overhead |

|

Portability |

Highly portable across environments |

Less portable, OS-specific configurations |

|

Scalability |

Ideal for microservices and scaling |

Less suitable for rapid scaling |

|

OS support |

Must match host kernel (typically Linux-based) |

Can run any OS supported by hypervisor |

|

Use cases |

Cloud-native apps, CI/CD, microservices, dev environments |

Legacy applications, monolithic systems, full OS testing |

How Docker works: An overview of key components

|

Component |

Description |

Key functions |

Example/Usage |

|

Docker Engine |

The core client-server application that manages containers |

Runs container lifecycle; handles image building and networking; provides CLI and REST API |

The Docker ‘run’ command starts a container via Docker Engine |

|

Docker image |

A read-only template with application code, dependencies, and libraries |

Blueprint for containers; pulled from Docker Hub or built locally |

Image like Python:3.10, or a custom image built with the Docker build command |

|

Docker |

A running instance of a Docker image, isolated from the host system |

Executes applications in isolation; shares host OS kernel; lightweight and fast |

Running Docker run python:3.10 starts a container with Python installed |

|

Dockerfile |

A text file with instructions to create a Docker image |

Defines how to build an image; includes base image, commands, dependencies, and startup script |

Sample line: FROM node:20 sets the base image to Node.js 20 |

What is a Dockerfile?

A Dockerfile is a plain text file that contains step-by-step instructions or commands to assemble a Docker image. Think of it as a recipe that tells Docker exactly how to build your image, layer by layer.

Using a Dockerfile means you can automate the image creation process, making it consistent, repeatable, and easy to share with others. Here’s an example of a Dockerfile.

Use official Python image as base FROM python:3.10 Set working directory WORKDIR /app Copy current directory contents to /app inside container COPY . . Install Python dependencies RUN pip install -r requirements.txt Make port 80 available to the world outside container EXPOSE 80 Define environment variable ENV ENVIRONMENT=production Run the app CMD [“python”, “app.py”]

Getting started with Docker

For basic installation in Windows and Mac, download and install ‘Docker Desktop’ from docker.com. For Linux, you can use your package manager. For example, on Ubuntu:

sudo apt-get update sudo apt-get install -y docker.io sudo systemctl start docker sudo systemctl enable docker

The first container run is:

docker run hello-world Building and Running Containers # Use official Python runtime as base FROM python:3.10-slim # Set working directory WORKDIR /app # Copy current directory contents into container at /app COPY . . # Install dependencies RUN pip install -r requirements.txt # Run the app when container starts CMD [“python”, “app.py”] Using Docker CLI # List running containers docker ps # List all containers (running and stopped) docker ps -a # Stop a container (replace CONTAINER_ID with actual ID) docker stop CONTAINER_ID # Remove a container docker rm CONTAINER_ID # Remove an image docker rmi IMAGE_NAME # View logs of a container docker logs CONTAINER_ID # Enter a running container interactively docker exec -it CONTAINER_ID /bin/bash

Key use cases of Docker

|

Use case |

Description |

How Docker helps |

Example |

|

DevOps |

Integrating development and operations for faster, reliable software delivery |

Consistent environments across dev, test, and production; automates deployment; simplifies rollback and updates |

Using Docker containers to package apps and automate deployment via tools like Jenkins, GitLab CI, or CircleCI |

|

Microservices |

Architecting applications as a collection of loosely coupled, independently deployable services |

Isolates each microservice in its own container; simplifies scaling individual services; enables polyglot environments |

Running separate containers for authentication, payments, and user profiles that can be developed and scaled independently |

|

CI/CD pipelines |

Automating code integration, testing, and deployment to deliver software rapidly and reliably |

Provides consistent test environments; speeds up build and test phases with reusable container images; supports parallel testing |

Running automated tests inside containers during each commit, then deploying containerised apps seamlessly |

Limitations and considerations

Although Docker has altered the ways in which software is developed and deployed, there are some limitations and considerations to keep in mind while adopting it.

For one, security can be an issue since the containers share the host operating system’s kernel. This matrix sharing of resources can increase the overall attack surface if containers are poorly isolated or configured. Organisations should follow best security practices, such as using minimal base images, running containers with least privilege, and regular vulnerability scans.

Performance-wise, the overhead is generally low for containers compared to bare metal applications, though it does exist. If an application has extremely high I/O or specialised hardware requirements, this overhead can become noticeable.

Another major consideration is data persistence. Since containers are ephemeral in nature and can be spun up or destroyed at a moment’s notice, there is one more variable to consider when persisting data — the application side of Docker volumes and bind mounts — leading to complexity in storage management.

Docker networking has its complexities when containers must cross multiple hosts or large multi-container applications are to be managed. Setting up container networks and assuring communication are complex endeavours, involving quite a steep learning curve.

When not to use Docker

Despite its advantages, Docker may not be suitable in some situations. GUI-intensive or desktop applications are one example. Containers truly run best when it comes to server-side and CLI applications, while graphical apps inside containers are rather poor performers and suffer from integration issues.

Applications requiring full OS feature sets or custom kernels are another case where Docker falls short. Since containers share the OS kernel of the host, apps that require custom kernel modules or deeper integration with the OS cannot really run inside containers.

Docker can seriously add unnecessary weight and complexity to very simple or small projects, especially those that don’t have any complicated deployment needs. In these special scenarios, more traditional ways of deployment may be simpler and more effective.

Legacy applications with complicated state management or licensing constraints may run into difficulties with containers, either in terms of technical requirements or the legal constraints.