Learn the fundamentals of quantum computing, including its core principles, how it differs from conventional computing, and its immense potential across industries.

In an era where data drives discovery and computation fuels innovation, the limits of classical computing are becoming increasingly clear. As problems in cryptography, drug discovery, climate modelling, and artificial intelligence grow exponentially complex, even the most powerful supercomputers struggle to keep pace. Enter quantum computing—a revolutionary paradigm that harnesses the powerful laws of quantum mechanics to process information in ways unimaginable to classical systems.

Unlike traditional computers that operate using bits—tiny switches representing either 0 or 1—quantum computers use qubits, which can exist in multiple states simultaneously through superposition. When combined with entanglement, a phenomenon that links qubits across space, quantum systems can perform vast parallel computations, unlocking solutions to problems once thought unsolvable.

Quantum computing may sound abstract or even futuristic, but its foundations are here today—and its impact is already unfolding. Let’s uncover how this quantum revolution is redefining the future of computation.

What makes quantum computers unique?

What sets quantum computing apart from every computing model before it is its foundation in quantum mechanics, the science governing nature at the smallest scales—where particles behave in ways that defy classical logic. This unconventional behaviour gives quantum computers abilities that traditional systems cannot replicate.

From bits to qubits

Classical computers use bits as their basic unit of information, each representing either a 0 or a 1. Every calculation, no matter how complex, is built on combinations of these binary states. Quantum computers, in contrast, use qubits—quantum bits—that can exist as 0, 1, or both simultaneously. This phenomenon, known as superposition, allows a quantum computer to explore many possibilities at once. Imagine trying to solve a maze: a classical computer checks one path at a time, but a quantum computer can analyse all paths simultaneously, greatly accelerating certain computations.

Superposition: Many states at once

A qubit’s ability to be in multiple states enables massive parallelism. For example, while two classical bits can represent one of four possible combinations at any given time, two qubits can represent all four combinations simultaneously. As the number of qubits grows, this parallel capacity expands exponentially, offering potential solutions to problems far beyond the reach of classical processors.

Entanglement: Linking qubits beyond space

Another hallmark of quantum computing is entanglement—a mysterious correlation between qubits such that the state of one instantly affects the other, no matter the distance between them. A simple analogy is a pair of magical dice that always show the same number, no matter how far apart they are rolled. This interconnectedness allows quantum computers to coordinate and process information in highly efficient ways, producing outcomes that rely on the collective behaviour of qubits rather than independent actions.

Quantum interference: Amplifying the right answers

Quantum algorithms also use interference, the ability of quantum states to reinforce or cancel out each other. This ensures that correct solutions are strengthened while incorrect ones are diminished. It’s like tuning an orchestra so that only the harmonious notes resonate—leading to more accurate results.

Why it matters: Transformative applications

These unique properties aren’t just theoretical marvels—they have profound real-world potential. Quantum computing could revolutionise:

- Cryptography: Breaking classical encryption or creating unbreakable quantum-secure codes.

- Optimisation: Solving logistics, scheduling, and supply chain problems faster than any classical algorithm.

- Drug discovery: Simulating molecules and chemical interactions with atomic precision.

- Artificial intelligence: Accelerating machine learning through quantum-enhanced data processing.

Quantum computers don’t simply run faster—they think differently. They tackle specific classes of problems (like factoring large numbers or searching unsorted databases) exponentially faster than classical systems. While they won’t replace conventional computers for all tasks, they will complement them in solving challenges that today’s machines cannot feasibly handle.

In essence, what makes quantum computing unique is its departure from binary certainty into a world of probabilistic power—where information exists in multiple states, relationships transcend distance, and interference steers computation towards truth.

Understanding qubits

At the heart of quantum computing lies the quantum bit, or qubit. While a classical bit can exist in one of two definite states—either 0 or 1—a qubit can exist in a state that is both 0 and 1 at the same time, thanks to the unique properties of quantum physics. Imagine a coin spinning in the air: instead of being heads or tails, it is both until it lands. Similarly, a qubit’s state is not fixed until it is measured.

Qubits can be realised using various physical systems, such as electrons, photons, or even atoms. For instance, the spin of an electron (up or down) or the polarisation of a photon (horizontal or vertical) can represent the two states of a qubit. By manipulating these systems, scientists can create and control qubits, paving the way for quantum computations.

Comparing classical and quantum computing

The distinction between classical and quantum computing is not merely academic; it has profound implications for what problems can be solved and how efficiently.

Classical computers process information using transistors that represent binary states (0 or 1). They are highly efficient for a wide range of everyday tasks—word processing, web browsing, and even complex simulations. Quantum computers, by contrast, leverage superposition and entanglement to process information in fundamentally new ways. They are ideally suited for solving certain types of problems that are practically insurmountable for classical computers.

The table below highlights the differences between classical and quantum computing.

| Basis of difference | Classical computing | Quantum computing |

| Basic unit of data | Bit – can be either 0 or 1 | Qubit – can be 0, 1, or both simultaneously (superposition) |

| Computation model | Deterministic – follows definite logical operations | Probabilistic – operates using probabilities and quantum states |

| Processing capability | Sequential or limited parallelism | Massive parallelism due to superposition and entanglement |

| State representation | Single state at a time | Multiple states at once |

| Interdependence | Independent bits | Entangled qubits are correlated across distances |

| Error handling | Uses classical error correction methods | Requires quantum error correction due to fragile qubit states |

| Algorithms | Classical algorithms (e.g., binary search, sorting) | Quantum algorithms (e.g., Shor’s, Grover’s) offering exponential or quadratic speedup |

| Hardware components | Transistors, silicon chips | Quantum processors using superconducting circuits, trapped ions, or photons |

| Energy consumption | Relatively high due to heat dissipation | Potentially lower for specific tasks, but requires extreme cooling (near absolute zero) |

| Applications | General-purpose computing: office tasks, internet, AI, databases | Specialised tasks: cryptography, optimisation, quantum simulation, machine learning |

| Scalability | Mature, scalable with Moore’s Law (though slowing) | Emerging, scaling limited by qubit stability and decoherence |

| Nature of output | Definite and deterministic | Probabilistic; requires measurement and statistical analysis |

| Computation speed | Linear or polynomial time for most problems | Exponential speedup for certain problem classes |

Quantum gates and circuits: The building blocks

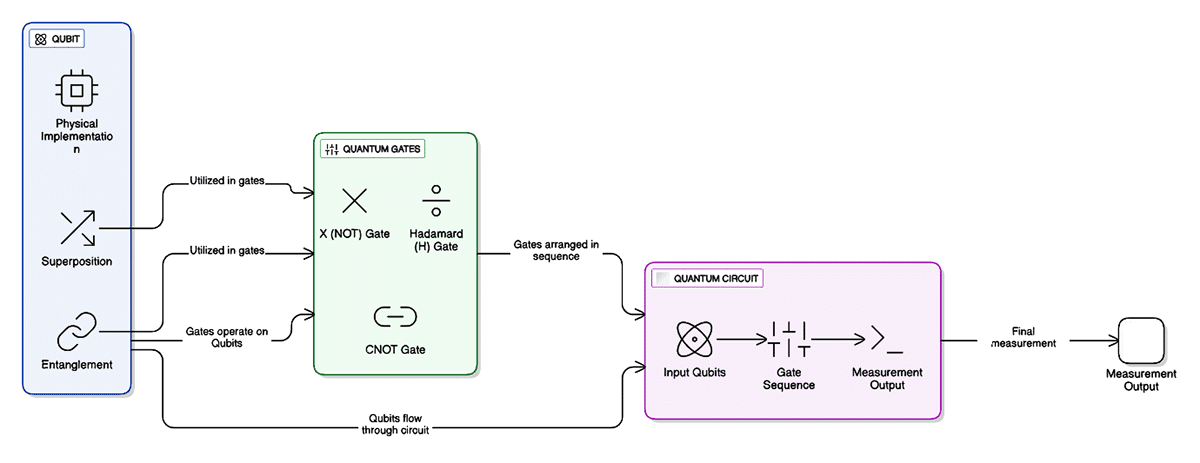

Just as classical computers use logic gates (AND, OR, NOT) as the building blocks of circuits, quantum computers use quantum gates. These gates manipulate qubits through operations that exploit quantum phenomena. Some common quantum gates include:

- Hadamard gate (H): Creates superposition by turning a definite state (0 or 1) into a combination of both.

- Pauli-X gate: Similar to a classical NOT gate, it flips the state of a qubit.

- CNOT gate (Controlled-NOT): Entangles two qubits, flipping the second qubit if the first is in state 1.

Quantum circuits are formed by arranging these gates in sequence, enabling the execution of complex quantum algorithms. For example, a simple quantum circuit might take an input qubit, place it in superposition with a Hadamard gate, and then entangle it with another qubit using a CNOT gate.

Decoding quantum algorithms

Quantum algorithms are specially crafted procedures that exploit the unique properties of quantum computers to solve problems. While the mathematics behind them can be intricate, the basic idea is to use superposition and entanglement to explore many possible solutions at once.

A classic example is Grover’s algorithm, which can search an unsorted database much faster than any classical algorithm. For instance, if you had to find a specific name in a phone book with 10 million entries, a classical computer might check, on average, 5 million entries before finding the right one. Grover’s algorithm, running on a quantum computer, could locate the correct entry in just about 10,000 steps—a dramatic speed-up. Another well-known algorithm is Shor’s algorithm, designed to factor large numbers efficiently. This has significant implications for cybersecurity, as much of modern encryption depends on the difficulty of this task for classical computers.

Beyond these, quantum algorithms are being developed for optimisation, machine learning, and simulation of physical systems—areas where quantum computers could eventually outperform their classical counterparts.

Example quantum algorithm: Grover’s search algorithm

One of the most elegant and widely taught quantum algorithms is Grover’s search algorithm, designed by Lov Grover in 1996. It demonstrates how quantum computing can offer a significant speedup for solving unstructured search problems—an area where classical computers struggle.

The problem

Imagine you are searching for a specific item in an unsorted database with N entries—for example, finding one name in a list of a million without any sorting or indexing.

- A classical computer must check each entry one by one, taking on average N/2 steps, or (O(N)) time.

- Grover’s algorithm, using quantum parallelism, can locate the correct entry in approximately √N steps, an enormous improvement for large datasets.

Quantum principles at work

Grover’s algorithm leverages three core quantum mechanics principles.

Superposition: Represents all possible database entries simultaneously.

Interference: Amplifies the probability of the correct answer while diminishing incorrect ones.

Measurement: Collapses the system to reveal the most probable solution—the desired item.

Step-by-step conceptual overview:

Step 1 – Initialisation: The algorithm begins by placing all possible states (entries) into superposition. This means the quantum computer considers every entry at once rather than sequentially.

Step 2 – Oracle function: An ‘oracle’ is a black-box function that can identify whether a particular state is the correct solution. When applied, it flips the sign of the correct state’s amplitude without revealing which one it is.

Step 3 – Amplification (Grover iteration): Through a process called amplitude amplification, the algorithm increases the probability of the correct answer while reducing the likelihood of incorrect ones. It achieves this using interference, combining wave-like quantum states constructively for the correct answer and destructively for others.

Step 4 – Repetition: The Grover iteration is repeated approximately √N times. After each iteration, the probability of measuring the correct solution grows.

Step 5 – Measurement: Finally, the system is measured, collapsing the quantum superposition into a definite state. The correct answer appears with high probability.

Classical vs quantum efficiency: Here’s the comparison:

| Aspect | Classical search | Grover’s quantum search |

| Search space size | (N) | (N) |

| Steps required | (O(N)) | (O(\sqrt{N})) |

| Efficiency gain | Linear | Quadratic |

While this may seem modest compared to exponential speedups (like in Shor’s algorithm), the quadratic improvement becomes transformative as (N) grows.

Real-world implications: Grover’s algorithm shows the quantum advantage in search and optimisation problems. Potential applications include:

- Database searching

- Pattern recognition

- Cryptanalysis (e.g., accelerating brute-force attacks)

- AI optimisation tasks

Though it doesn’t make encryption instantly obsolete, Grover’s algorithm emphasises the need for quantum-resistant cryptography, as it can halve the effective key length of symmetric encryption methods like AES.

Why it matters

Grover’s algorithm illustrates how quantum mechanics transforms computation. Instead of processing each possibility one by one, a quantum computer explores all options simultaneously, using interference to zero in on the answer. It exemplifies the power of quantum parallelism and stands as a cornerstone example of how quantum computing outpaces classical logic in specific domains.

The roadmap for quantum technologies

Quantum computing today stands at a pivotal point—an intersection between theoretical promise and emerging reality. We are currently in what experts call the NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) era, characterised by quantum processors with tens to hundreds of qubits. These systems can perform limited computations but are still constrained by noise, instability, and error rates that hinder large-scale, reliable applications.

Despite these challenges, the roadmap for quantum technologies is unfolding across three progressive phases.

Short-term (present to 3 years): NISQ applications and hybrid approaches: The immediate focus is on harnessing current quantum devices for practical, small-scale problems. Researchers are developing hybrid quantum-classical algorithms—such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA)—that combine quantum advantages with classical optimisation.

Key objectives include:

- Reducing qubit noise and improving coherence time.

- Enhancing error mitigation (though not full correction yet).

- Demonstrating quantum advantage on niche industrial tasks (e.g., molecular modelling, portfolio optimisation).

Leading players like IBM, Google, Rigetti, IonQ, and D-Wave are offering cloud-based quantum access, enabling developers and researchers worldwide to experiment with real hardware.

Mid-term (3-10 years): Fault-tolerant quantum computing: The next milestone is achieving fault-tolerant systems—quantum computers capable of correcting errors automatically and maintaining stability over long computations.

This phase will likely see:

- Implementation of quantum error correction codes.

- Scalable architectures exceeding thousands of logical qubits.

- Specialised processors for chemistry, materials science, and secure communications.

Collaboration between academia, industry, and governments—such as the US National Quantum Initiative, EU Quantum Flagship, and China’s quantum strategy—is accelerating progress in hardware, software, and ecosystem development.

Long-term (10+ years): Quantum supremacy across domains: In the long run, the goal is universal quantum computing—machines capable of outperforming classical supercomputers in a broad range of tasks. Expected breakthroughs include:

- Fully fault-tolerant quantum architectures.

- Integration with quantum networks and quantum internet for ultra-secure communication.

- Real-world impact in drug discovery, climate modelling, cryptography, AI, and logistics optimization.

By this stage, quantum computing will transition from laboratory prototypes to commercially viable platforms, integrated into enterprise and national infrastructure.

The roadmap is not just technical. Building a sustainable quantum future requires:

- Standardisation of programming languages, benchmarks, and interfaces.

- Talent development through education and training programmes.

- Ethical frameworks ensuring responsible use, data privacy, and equitable access.

Global collaboration will be crucial—no single nation or company can realise quantum’s potential in isolation.

Quantum technologies are evolving rapidly, yet their full potential remains on the horizon. Like the early days of classical computing, today’s limitations are stepping stones towards tomorrow’s breakthroughs. With sustained investment, interdisciplinary research, and open collaboration, the quantum revolution will reshape computation, security, and innovation across the 21st century.