Discover why public-key cryptography is a powerful mechanism for secure key exchange in this 12th part of the series of articles on SageMath.

In the previous article in this series (published in the September 2025 issue of Open Source For You, we explored RSA in detail and implemented a simplified yet practically secure version of it. Unlike the toy examples we had considered earlier, this implementation can be executed even on moderately powered computers, yet remains unbreakable with the resources of the most powerful supercomputers available today. However, we also observed that RSA, like most public key cryptographic (PKC) systems, is computationally intensive and therefore not well suited for large-scale data encryption. In practice, PKC is typically employed to encrypt short messages or, more importantly, to securely exchange secret

keys between two parties. Once exchanged, these keys are then used in symmetric-key cryptography, which is significantly faster and better suited for encrypting large volumes of data. This combination makes public-key cryptography a powerful mechanism for secure key exchange—an area that will be the central focus of this article.

Before moving further, let us revisit another thread we began developing in the previous article—why SageMath is faster and more efficient than Python? In that discussion, we examined examples that highlighted the syntactical differences between SageMath and Python, demonstrating that SageMath is not merely another dialect of Python. We also observed cases where SageMath provided significant speedups while performing operations similar to those in Python.

We concluded that this performance advantage arises because SageMath leverages specialised mathematical libraries such as FLINT (Fast Library for Number Theory) and GMP (GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library). As promised, in this article we will continue exploring this topic by discussing additional specialised libraries and back-end tools that empower SageMath to deliver superior performance compared to other languages commonly used in scientific computing, such as Python and Julia.

Let us now take a moment to introduce Julia. Julia is a modern, general-purpose programming language released in 2012, developed with a strong focus on scientific and numerical computing. In one of my earlier articles for OSFY, published as part of a series on AI, I compared the performance of Julia with Python. The article is available online on the OSFY portal at https://www.opensourceforu. com/2023/07/ai-beyond-python. If you read it, you will see that Julia clearly outperforms Python when performing similar tasks. Now, let us set up a competition between SageMath and Julia to see who wins.

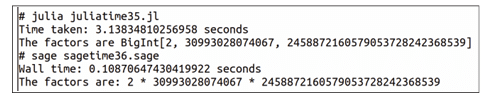

Factoring a large integer serves as a good test case, given its direct relevance to our ongoing discussion of public-key cryptography (PKC). The Julia program named ‘juliatime35. jl’ shown below measures the time taken to compute the factors of a very large integer stored in a variable named n.

using Primes n = big”152415787806736785461057782810547205156226” start = time( ) factors = factor(n) f inish = time( ) println(“Time taken: $(finish - start) seconds”) factor_list = collect(keys(factors)) println(“The factors are $factor_list”)

The SageMath program named ‘sagetime36.sage’, shown below, performs the same operations as the Julia program ‘juliatime35.jl’.

n = 152415787806736785461057782810547205156226 t0 = walltime( ) factors = factor(n) print(“Wall time:”, walltime(t0), “seconds”) print(“The factors are:”, factors)

Upon executing the programs ‘juliatime35.jl’ and ‘sagetime36.sage’, the outputs shown in Figure 1 are obtained. The output clearly shows that in the speed ‘competition’,

SageMath knocked out Julia, with SageMath enjoying roughly a 29-fold advantage. Moreover, as the size of the number stored in the variable n increases, SageMath’s performance advantage becomes even greater.

While Julia is widely recognised as a fast programming language for scientific and numerical computing, SageMath holds a distinct advantage in certain domains—particularly in number theory and integer factorisation. This is because SageMath integrates highly optimised external libraries such as PARI/GP and ECM under the hood, which are renowned for their efficiency in handling large integers. In contrast, Julia’s built-in factor( ) function, provided by the package Primes.jl, tends to be significantly slower when dealing with large numbers.

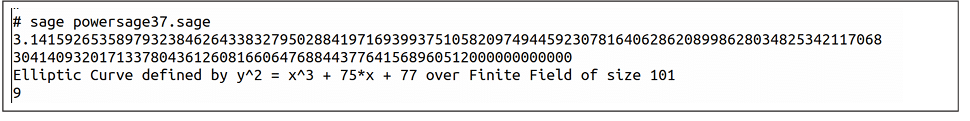

Now, let us explore a few examples that showcase the power of PARI/GP and ECM directly, rather than letting them work quietly behind the scenes. To illustrate this, consider the SageMath program ‘powersage37.sage’, which executes two PARI/GP one-liners and two ECM one-liners, demonstrating their capabilities in action.

print(pari(“default(realprecision,100); Pi”)) print(pari(“50!”)) print(EllipticCurve(GF(101), [randint(0,100), randint(0,100)])) print(EllipticCurve(GF(101), [0, 0, 1, -1, 0]).random_ point().order())

Now, let us try to understand the one-liners. The first one-liner uses PARI/GP to compute a high-precision value of π, while the second one-liner computes the factorial of a large number using PARI/GP. The third and fourth one-liners perform operations on elliptic curves using ECM, a special type of curve with numerous applications in public-key cryptography (PKC). A full theoretical explanation of elliptic curves is beyond the scope of this series, but these examples clearly demonstrate the power of ECM and its capabilities within SageMath.

Upon executing the program ‘powersage37.sage’, the output shown in Figure 2 is obtained. As the figure illustrates, the integration of PARI/GP and ECM provides SageMath with a significant boost in computational power and versatility.

Diffie–Hellman key exchange

Now, it is time for us to go back to a period even before the birth of RSA — a time when the very concept of public key cryptography did not exist. In the early 1970s, two computer scientists, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, were grappling with a fascinating problem: How can two parties securely exchange a secret key over an insecure communication channel? Their collaboration led to the groundbreaking Diffie–Hellman (DH) key exchange protocol, introduced in 1976. This was the first practical method that allowed two people to establish a shared secret key without having met or exchanged anything privately beforehand — a truly revolutionary idea for its time.

However, while their discovery laid the foundation for modern cryptography, Diffie and Hellman stopped short of realising that the same mathematical principles could also be used to create a system for direct encryption and digital signatures. In other words, they solved the problem of secure key exchange, but not secure message encryption using public and private keys. It was only later, in 1977, that Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman at MIT took the next leap by inventing the RSA algorithm, which implemented the full idea of public key cryptography (PKC) — a concept that Diffie and Hellman had unknowingly set the stage for.

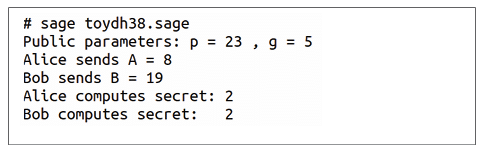

Now, consider the SageMath program named ‘toydh38. sage’, which implements a toy version of the Diffie–Hellman key exchange. In this example, small numbers are used to make the underlying process easy to follow and to help visualise how the Diffie–Hellman key exchange works in principle.

p = 23 g = 5 a = 6 A = power_mod(g, a, p) b = 15 B = power_mod(g, b, p) S_alice = power_mod(B, a, p) S_bob = power_mod(A, b, p) print(“Public parameters: p =”, p, “, g =”, g) print(“Alice sends A =”, A) print(“Bob sends B =”, B) print(“Alice computes secret:”, S_alice) print(“Bob computes secret: “, S_bob)

Now, let us understand how the program works. The prime number p = 23 and the primitive root g = 5 act as public parameters. Alice selects her private key a = 6 and computes her public value A = ga mod p, while Bob selects his private key b = 15 and computes his public value B = gb mod p. They exchange A and B over an insecure channel. Alice then calculates the shared secret S_alice = Ba mod p, and Bob calculates S_bob = Ab mod p. Both arrive at the same shared secret, which can be used as a common key for secure communication. The security of the key exchange lies in the fact that neither Alice’s nor Bob’s secret key is ever transmitted over the insecure channel.

Upon executing the program ‘toydh38.sage’, the output shown in Figure 3 is obtained. The figure clearly shows that both Alice and Bob arrive at the same secret key, confirming the successful execution of the Diffie–Hellman key exchange.

Now, let us implement a more realistic version of the Diffie–Hellman key exchange that is practically secure. The SageMath program named ‘dh39.sage’ shown below demonstrates a simplified yet powerful implementation capable of generating and exchanging keys that are more than 150 digits long.

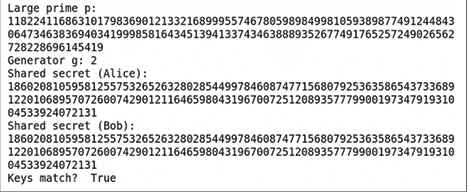

p = random_prime(2^512, lbound=2^511) g = primitive_root(p) a = ZZ.random_element(2, p-1) A = power_mod(g, a, p) b = ZZ.random_element(2, p-1) B = power_mod(g, b, p) S_alice = power_mod(B, a, p) S_bob = power_mod(A, b, p) print(“Large prime p:”, p) print(“Generator g:”, g) print(“Shared secret (Alice):”, S_alice) print(“Shared secret (Bob): “, S_bob) print(“Keys match? “, S_alice == S_bob)

Now, let us understand how the program works. It firstgenerates a random 512-bit prime number p and a primitive root g modulo p. Alice and Bob each select their private keys a and b randomly between 2 and p-1, then compute their public values A = ga mod p and B = gb mod p. They exchange these public values and use them to compute the shared secret key: Alice calculates S_alice = Ba mod p and Bob calculates S_bob = Ab mod p. The program prints the large prime p, the generator g, both computed shared secrets, and confirms that the keys match, demonstrating a successful secure key exchange.

I was unable to run the program ‘dh39.sage’ locally on my computer due to the intensive computations involved. Therefore, I relied on CoCalc to execute the program, which produced the results effortlessly. Recall that we introduced CoCalc at the beginning of this series, so I will not go over the execution steps again. Unless you have access to a very powerful system, it is advisable to run this program on CoCalc for convenience and efficiency.

Upon executing the program ‘dh39.sage’ on CoCalc, the output shown in Figure 4 is obtained. The figure clearly shows that the keys computed by both Alice and Bob are identical. It can also be observed that the shared key is more than 150 digits long, corresponding to a 512-bit key. Although a 512-bit key is no longer considered secure against modern computational power, the same program can easily be modified to generate much larger keys, thereby enhancing security.

Now it is time to wrap up our discussion—but our journey with public-key cryptography (PKC) is far from over. Consider the following scenario: you receive an email from a friend who promises to lend you `1 million. Later, your friend insists that he never sent such a message and that someone must have spoofed his email address. How can you verify that the email truly came from your friend? Clearly, there must be a way to ensure the authenticity and integrity of digital communication. This is where digital signatures come into play. Once again, PKC provides the foundation—enabling us to sign documents and messages securely in the digital world. In the next article in this series, we will explore digital signatures, along with the related concepts of hashing and message authentication.