This article introduces a few concepts of functional programming, and the constructs in Python that are useful for it. It is aimed at those with a basic understanding of Python (like Python prompt, lists, etc).

Functional programming has its origin in lambda calculus, a formal system used for function definition, which has now emerged as a useful tool in the investigation of problems in the field of computability or recursion theory, and as the basis for functional programming. Lambda calculus was introduced in the 1930s by Alonzo Church and Stephen Cole Keene as a part of their investigations into the foundations of mathematics, and is one of the many examples showing that computer science has its basis in mathematics.

Functional programming is a programming paradigm that treats calculations and computations as the evaluation of functions rather than state and mutable data, as opposed to Imperative Programming. In other words, the emphasis is on functions and their evaluation, rather than achieving results by directing the program through a variety of states, which is achieved in different methods. In simpler terms, variables, data structures, I/O, and assignments whose values at each execution determine the state (which leads to reliability issues) are avoided.

In pure functional languages, I/O, assignments, etc., are completely avoided. In Python, however, we do not avoid them completely. Instead, a functional-like interface is provided, but internally, non-functional features are used. For example, local variables are used inside the function, but global variables outside the function will not be modified.

Functional programming can be regarded as the opposite of object-oriented programming. Objects are entities that provide functions to modify internal variables (and hence internal state). Functional programming aims at the complete elimination of state (as much as possible), and works with the data flow between functions.

In Python, it is possible to combine object-oriented and functional programming. For example, functions could receive and return instances of objects.

The advantages of functional programming

A main feature of functional programming is the use of pure functions (functions that return the same output every time, for the same input). A simple example is the function sinx, which returns the same output for the same input, as opposed to the function today, which returns different values depending on when it is executed.

Another feature is that functions are first-class objects, i.e., they can be created dynamically and can be passed as arguments to, and even returned as values from, functions.

A key feature of functional programming is referential integrity, i.e., the lack of side effects. The execution of functions does not affect state, and hence eliminates deviation from the intended behaviour. This means that it is much easier to verify, parallelise and optimise programs, as well as write automated tools to perform the same tasks.

There are several theoretical and practical advantages of functional programming, which are beyond the scope of this article. Please refer to the links provided at the end of the article in the References section.

Functional programming in Python

In this section, I will cover a few constructs that enable writing functional style programs in Python. All code in this section was run on Python 2.6.6 over GCC 4.4.5 in Ubuntu 10.10.

Iterators

Let’s start by looking at an important foundation for writing functional-style programs in Python: iterators. These are objects that represent a stream of data, and return one data element at a time. These are extremely useful in manipulating lists, tuples, strings, etc. Python has a built-in function iter(), which takes an object and returns an iterator to it.

Consider the following code, which creates an iterator object, it, for the list L. Notice how each element is accessed using the next() method of the iterator object.

>>> L = [1,2,3] >>> it = iter(L) >>> print it <listiterator object at 0x7f1ec1f9f550> >>> it.next() 1 >>> it.next() 2 >>> it.next() 3 >>> it.next() Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in ? StopIteration >>>

Note: If iter() raises a TypeError, it means that the object passed to it doesn’t support iteration.

Iterators are most commonly used in for statements in Python, as shown below:

for i in iter(alist): print i

Another way of achieving the same is as follows:

for i in alist: print i

Calling iter() on a dictionary returns an iterator that loops over the keys:

>>> monthList={'Jan' : 1, 'Feb' : 2, 'Mar' : 3, 'Apr' : 4, 'May' : 5, 'Jun' : 6, 'Jul' : 7, 'Aug' : 8, 'Sep' : 9, 'Oct' : 10, 'Nov' : 11, 'Dec' : 12}

>>> for key in monthList:

... print key, monthList[key]

Feb 2

Aug 8

Jan 1

Dec 12

Oct 10

Mar 3

Sep 9

May 5

Jun 6

Jul 7

Apr 4

Nov 11

Note: The order is based on the hash ordering of objects in the dictionary and, hence, the random output.

List comprehensions

List comprehensions are easy ways of generating lists. Consider the following code to generate a list containing numbers from 1 to 25:

>>> alist=[] >>> for i in range(1, 26): ... alist.append(i) >>> alist [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]

An alternative, functional approach to the same would be as follows:

>>> alist=[i for i in range(1, 26)] >>> alist [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]

Notice that this code is more intuitive and easy to understand — it is close to plain English!

Another example — how to strip white-space from a list of strings:

>>> alist=[' This is line 1 \n', 'This is line 2 \n', '', ' This is line 3\n'] >>> [line.strip() for line in alist] ['This is line 1', 'This is line 2', '', 'This is line 3']

Here’s a modification of the above, which tests if a string is a null string, and doesn’t print if that is the case.

>>> [line.strip() for line in alist ... if line != ''] ['This is line 1', 'This is line 2', 'This is line 3'] >>>

The actual syntax of list comprehension is as follows:

[ expression for expr in sequence1 if condition1 for expr2 in sequence2 if condition2 for expr3 in sequence3 ... if condition3 for exprN in sequenceN if conditionN ]

The equivalent Python code for the above is shown below:

for expr1 in sequence1: if not (condition1): continue # Skip this element for expr2 in sequence2: if not (condition2): continue # Skip this element ... for exprN in sequenceN: if not (conditionN): continue # Skip this element # Output the value of the expression.

While creating tuples in list comprehensions, it must be surrounded by parentheses. In the following example, the first list comprehension results in an error, while the second one is correct:

>>> seq1=[1,2,3] >>> seq2=['a','b','c'] >>> [x, y for x in seq1 for y in seq2] File "<stdin>", line 1 [x, y for x in seq1 for y in seq2] ^ SyntaxError: invalid syntax >>> [(x, y) for x in seq1 for y in seq2] [(1, 'a'), (1, 'b'), (1, 'c'), (2, 'a'), (2, 'b'), (2, 'c'), (3, 'a'), (3, 'b'), (3, 'c')]

Map

Map is a built-in function that takes a function and a list as an argument, applies the function to each element of the list, and returns the output. For instance, map(f, iterA, iterB, ...) returns a list containing f(iterA[0], iterB[0]), f(iterA[1], iterB[1]), f(iterA[2], iterB[2]),… For example, the following code finds the square of each element in a list:

>>> def square(x): ... return x*x >>> alist=[1,2,3,4,5] >>> map(square, alist) [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

The same output can be achieved with list comprehension:

>>> [square(element) for element in alist] [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

Filter

As the name suggests, filter returns those elements that satisfy a particular condition. For example, the following code filters out all the even numbers:

>>> def iseven(x): ... return x%2 == 0 >>> alist=[1,2,3,4,5] >>> filter(iseven, alist) [2, 4]

The same output can be achieved with list comprehension as follows:

>>> [x for x in alist if iseven(x)] [2, 4]

Note: map() and filter() are somewhat obsolete, but they have been explained since they are the fundamental concepts of functional programming. The itertools module provides the functions imap() and ifilter(), which perform the same function. Readers are encouraged to refer to the Python documentation for more on itertools.

Lambda

The lambda statement allows one to create functions on the fly, i.e., functions that are not bound to a name. It is most commonly used with map(), filter(), etc. Lambda can be used to replace several small functions, and thus save a lot of unnecessary code. Consider the iseven() function defined above. It can be replaced by a lambda statement as follows:

>>> alist=[1,2,3,4,5] >>> filter(lambda x: x % 2 == 0, alist) [2, 4]

Similarly, the code example for map() can be rewritten as:

>>> alist=[1,2,3,4,5] >>> map(lamdba x: x * x, alist) [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

As an example of how useful and powerful the lambda statement can be, here is the implementation of “Sieve of Eratosthenes”:

>>> numbers=range(2,50) >>> for i in range(2,8): ... numbers=filter(lambda x: x == i or x % i, numbers) >>> numbers [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 47]

Thus, the lambda statement can be combined with map(), filter(), etc., to produce numerous powerful computations in very small statements. Lambda is rather limited in the functions that it can define; put too much into a lambda statement, and it’ll get complicated and hard to understand what is going on. Notice that without lambda, the code below is much easier to understand:

total = reduce(lambda a, b: (0, a[1] + b[1]), items)[1] total = 0 for a, b in items: total += b

Thus, it’s best to use lambda sparingly, and with discretion.

Future of functional programming

Although this approach has several problems related to CPU efficiency, memory efficiency, etc., it definitely has a good future, due to the fact that it plugs many loopholes in currently existing paradigms. Also, since it avoids program states, it is believed to be best suited for concurrent programming, which is very important these days due to the advent of multicore processors. Ultimately, it’s a trade-off between efficiency and guaranteed performance — functional programming, although inefficient, ensures proper performance, while the other approaches have a high degree of unpredictability in the states they will assume. We must wait and see which comes out on top.

References

- Wikipedia reference on functional programming

- Python documentation on functional programming

- Python: Lambda Functions

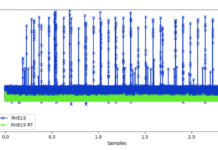

I once did a benchmark comparing the call to filter with the

construction of a comprehension list with an if condition. Filter is

much more slower. The reason ? because function calls are much heavier

than conditionnal branching.

So my advice is don’t use filter unless the filtering condition is complex and lengthy. Otherwise use comprehension lists with an if condition.