Automatic stub generation can significantly improve code analysis. Read on to find out why you should consider this, and how to go about it.

A good project takes a desired shape only due to the rigorous effort and time that developers put into it. But all this effort can go straight down the drain if the key components that are essential for development present any problems. During the development of the Toloka-Kit library at Toloka, the team encountered a wide range of such issues with integrated development environment (IDE) support. This article will help you understand the issues faced and how these were dealt with, so you can cross similar hurdles easily.

To put things into perspective, let us first understand what IDE hinting is.

IDE hinting

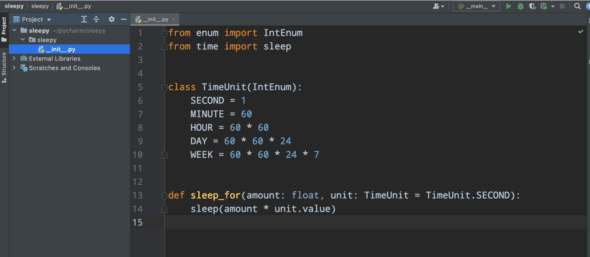

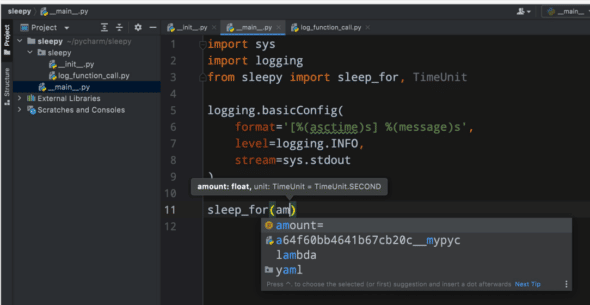

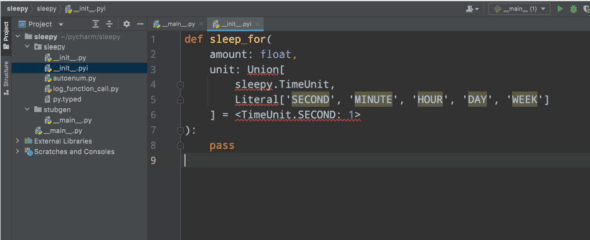

Let us say we want to implement a module called sleepy (Figure 1). This sleepy module will contain a sleep_for function between the standard library and time sleep function. Our sleep_for function will accept a time unit, so we will be able to make it sleep for different time periods, say half an hour, a day, or maybe even for weeks.

The team at Toloka implemented this module, and we saw that if we used the script_for function anywhere in our code, then the IDE showed us the signature. Upon trying to print the argument name it got autocompleted. If for some reason we passed an argument that was not expected in the signature, then the IDE highlighted this argument and we would see that we were doing something wrong before running the code.

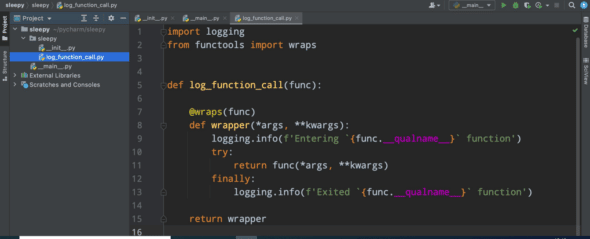

Let us write a simple decorator called log_function_call, as shown in Figure 2. This function does exactly what the name suggests. It will write a line of code in the login stream every time we run the function, and every time the function is complete we will write another message to our login form.

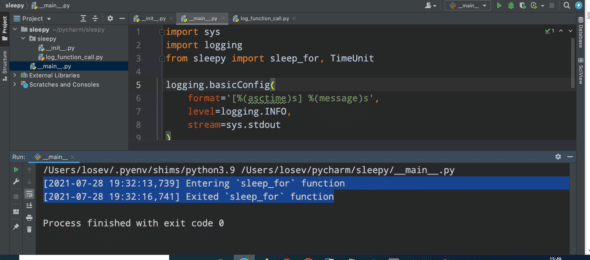

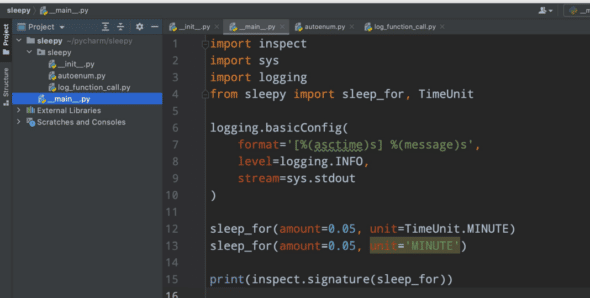

Now, if we configure our login and run our sleeper function, we can see that everything works just fine (Figure 3). We can clearly see these lines of code. If we start to use this function in our code, we can see that neither do we have the signature highlighted any longer nor are the arguments autocompleted. If we pass an argument that shouldn’t be there, it is not highlighted and IDE does not indicate that we are doing something wrong.

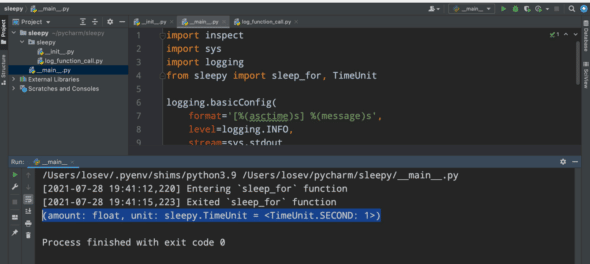

“What are the reasons for this?” you may ask. Technically, it seems perfectly fine behaviour because decorators are substituting one function for another. Here, we defined a function called ‘wrapper’ and substituted our original function with the wrapper function. Upon importing the inspect module, when we used the inspect.signature function to just view the signature, we could see that the signature is still there (Figure 4).

The trick is that functools.wrap actually preserves the signature in a specific attribute and it is there at runtime. And that begs the question: “Why could our IDE not pick the information up?”

Static code analysis

The reason for this is exactly what has been mentioned above. The information about the original signature is stored in an attribute and is available at runtime. But IDE does not run our code. Instead, it uses static code analysis; so it does not have access to runtime objects and there are plenty of reasons for that.

- Side effects: If you are running the code without proper knowledge of it, you may end up damaging your hard drive.

- Code may raise an exception or run for an infinite time: There could also be an exception in the code that can be raised while it’s being run.

- Syntactically incorrect code: The code may not be syntactically correct code.

In static code analysis, IDEs understand the code itself without actually running it, which is a much more difficult task to accomplish.

So what can we do?

Generally, it is the best practice to provide the IDE with as much information as possible in the code itself. But in this particular case, this is what can be done. Figure 5 shows what our original decorator looked like; we can provide additional information in the form of typing. We can tell our IDE that the log function call is accepting and returning something of the same type. In our case, if the log_function_call accepts a function with some signature, then it should return the function with the same signature.

Let us see how this works. If we start typing the argument name, we can see that there is a pop-up window above, which lists the whole signature (Figure 5). So actually the information about the signature is in our IDE but is not used to the fullest extent for some reason. The same is happening with the additional argument. The reason it does not highlight anything is due to some minor bug.

Even a simple decorator can confuse IDE hinting, but in real life we may want to implement some more difficult decorators that we would not be able to annotate properly to help IDE to cope with this.

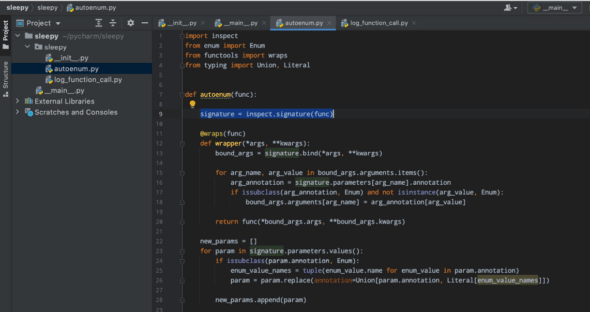

Let us go back to our sleeping module for a second, and say that we got some feedback from our users to ensure our function is good. The users do not want to import time units every time we use the module. They want to be able to use both TimeUnit enum and the string literal. So, we write another decorator called autoenum, which will take the function, analyse the signature, and pick the arguments that are annotated as enum types. For those particular arguments, we will try to cast all the arguments that pass to the enum value. The code will look something like what is shown in Figure 6.

The process is quite complicated, but let us go through it. First, we take the original signature of our function. Next, we bind our arbitrary arguments args and kwargs to the original signature in order to understand which values are passed to which argument name. Then we traverse the pairs of argument names and values passed to this argument. In case the argument was annotated as enum in the original signature, and if for some reason the value passed to this argument is not an enum, then we can assign a new argument, which is an argument annotation of original value. It takes an enum class and creates an enum instance from a string with a row name.

There is a big chunk of code that preserves the signatures. If we want our new function to accept both enums and string literals, then we must update the annotations so that every enum annotation is replaced with a union of enums and some string literals. We can recreate a signature object and assign it to a signature attribute.

In Figure 7, we can see that our IDE highlights the MINUTE string as an invalid argument, but if we run the code we can see that both versions of our code, i.e., the one with the time unit and the one with the string, are actually working. And when we try to get the output from the signature, we can see that this signature is actually updated.

As a unit we should be able to pass both the sleepy time unit, which is an enum, or one of the following with literal seconds, minutes, hours, days or weeks. For some reason, IDE does not take this and we know why.

In this particular case the code is so complicated that it is quite tough to understand which signature should be deduced from it without running it, because it is then almost equivalent to actually running the code. This is a very difficult problem, and we cannot think of annotations that will simplify the work for our IDE.

This is why stub files are proposed.

What are stub files?

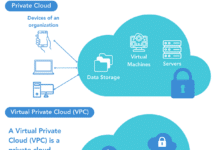

Stub files are special files containing PEP-84. The main purpose of these files is to hold the typing information for modules. They are just Python files with the extension ‘pyi’. If an IDE finds a corresponding stub file for a module, it will analyse the stub file instead of the original file for syntax highlighting.

What to add to stub files

What can be omitted?

|

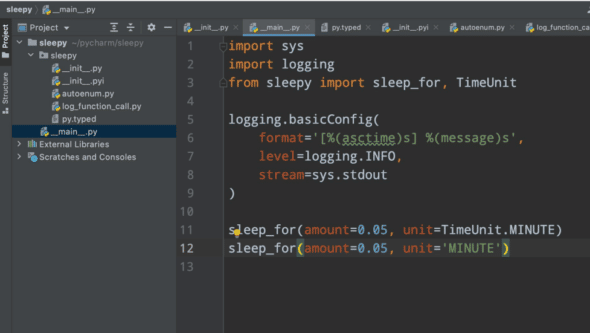

Now we have PEP-561, which says that any package maintainer that wants to support stub files has to put a marker file named py.typed in the package. We create an empty file called py.typed. This is an indicator for the static analytics tool for our IDE that it should look for the stub files in the package. Let’s see what happens to our IDE hinting after we add a py.typed empty file.

We can once again see the signature and the autocomplete. We typed an argument that is not there and it is still highlighted. If we pass a string instead of the Timeunit.num, you can see it is not highlighted as an error in Figure 8. But there is still a problem. The reason for using all those decorators was to eliminate the boilerplate so that our coding process could be simplified and there would be no need to write a new piece of code every time. We could put this logic to decorators, but to support the IDE correctly we need to maintain stub files all by ourselves. This is a huge burden and defeats the purpose of using the decorators in the code. This is where automatic stub generation comes in.

Automatic stub generation

To cut the long story short, the IDE is using static code analysis because it is afraid to run our code and does not have access to runtime objects to examine them. But if we write our code correctly while ensuring that it does not contain any side effects, and we can safely import it, then we can help the IDE to import these modules. From the imported modules we can inspect the module and create stub files without decorators, but the IDE will be able to pick it.

Let us write some code to see how this can be implemented:

import importlib.util

from inspect import isfunction, signature

from io import StringIO

from types import ModuleType

def load_module_from_file (name: str, path: str):

spec = importlib.util.spec_from_file_location (name, path)

module = importlib.util.module_from_spec(spec)

spec. loader.exec_module(module)

return module

def generate_stub_content (module: ModuleType) -> str:

sio = StringIO()

for name, value in module.__dict_.items():

if isfunction(value) and value.__module__== module.__name__:

sio.write(f’def {name}{signature (value)}:\n pass\n’)

return sio.getvalue()

def main(name, path):

with open (path + ‘i’, ‘w’) as stub_file:

module = load_module_from_file(name, path)

stub_file.write(generate_stub_content(module))

if __name__== ‘__main__’:

main(‘sleepy’, ‘../sleepy/__init__.py’)

First, we have a function that receives the name of a module and a path to a source code. It imports the source code from the path as if it was a module called name. We’ll see how this works later.

Next, we need to create a special function that generates the stub files so that this function will accept the module object. This is a simplified version but will only generate stub files for functions. We will take our module and traverse all the attributes of our modules. If the value that is stored in the attribute is a function, and this function was defined in a specified module (some modules might be imported from somewhere else), then we only want to create the stub files to create the functions that are defined in our module. We will write the keyword, the name of the function, the signature of the function, and an empty body. The only thing ‘Function main’ does is that it takes a path to a module and imports it, creates a stub file, and then writes this file into the file that ends with an ‘I’. Now if we take a sleepy dot ‘py’ module, it will write the stub file to sleepy.pyi and we can run the code for our sleepy module.

We want to import the sleepy module as a sleeper module, and it is located at sleepy/youNeedThatFile. We can get a long line of code by running it, but if we refactor the code we will see something like what is shown in Figure 9.

We now have the sleep_for function and a signature that is pretty much similar to what we expected but not quite. From this simple example we can see all the difficulties we will encounter while trying to take this approach.

This code was simple and did not generate a syntactically correct Python file. This was because there was a problem with the default value and the required files were also not imported for it to be a valid Python file. We did not import literal and union, or define sleepy.TimeUnit. But since the IDE is clear, with a little more effort we can easily make this code work.

In this case, we used the Stubmaker tool. This tool accepts the name and path to the package and output directories to generate stub files. This allows us to get automatically generated stub files that are created after introspecting the runtime objects.

It is essential to understand the need for proper code analysis while working on a project. Try to seal as many loopholes as possible, so that problems like low cohesion are overcome. Developer time is valuable, and should be spent on improving the project rather than fixing routine problems. So, go for automatic stub generation to make their life easier too.